The policies and the people that turned the red wave pink

Policy Postmortem

At MacIver, we believe policy matters and voters should expect candidates who have policy priorities and communicate their policy goals and plans. Good policy is good politics.

Each election cycle, there are a different set of policy matters in play that drive voter interest, engagement and turnout. This year large majorities of voters were deeply concerned not only about making ends meet in this time of historic inflation but were also on high alert about the threat of violence in our communities and the crisis in our education system.

The electorate deserves answers from candidates about how they will address the problems of the day every election cycle but needs those answers during times of turmoil.

Voters got little in the way of answers, and Wisconsin saw a return of ticket-splitting. In years past, ticket-splitting in Wisconsin was a time-honored, proud declaration of independence from lock-step adherence to a party line. This year, lacking much policy substance or consistency from challengers, voters seemed to choose incumbents whose record provided predictability if not perfection.

In a midterm election cycle where both parties expected to see a red wave, instead, we saw pink.

As the saying goes, elections have consequences, and the consequences for Wisconsin of the pink wave are another 4 years of divided government.

An unexpected outcome demands an explanation, and so far, the political pundits’ leading contenders are Trump, abortion, money, lack of money, dark money, good data, bad data, good targeting, bad targeting, good organization, poor organization, good messaging, and bad messaging. Political postmortems will fill airwaves, social media, column inches, and no doubt the inboxes of both the real-life and armchair strategists for months, maybe years to come.

This is a different postmortem, one examining the policies and the people that shaped the outcome in Wisconsin.

Pink Wave Policies

If polls are to be believed, and it has been more difficult to get a clear picture from polling in recent years, the issues worrying voters in the state this year were inflation, crime, public education, abortion, and taxes. The August and November Marquette polls showed little movement among likely voters on the issues:

| August | November | ||

| Inflation | 93% | Inflation | 91% |

| Public Education | 90% | Public Education | 89% |

| Crime | 88% | Crime | 85% |

| Taxes | 85% | Taxes | 84% |

| Abortion | 79% | Abortion | 80% |

In most years the top issues are not so tightly bunched with such overwhelming levels of voter concern. It is clear that this contributed to ticket-splitting – if a voter’s top concern left them without a clear choice, they almost certainly cared nearly as much about their number 2 and 3 issues and could use those to inform their choices.

Several years of incredibly tight races have led operatives and the media to consider virtually all voters as partisans. That misses the truth that most voters are not the card-carrying party faithful, and the voting landscape is shifting. What used to be the Republican stronghold of the WOW counties is sliding away, just as Northern Wisconsin is slipping away from the Democrats. Ignoring people and the policies they care about isn’t a long term strategy for political success.

Wisconsin had a long, strong history of ticket-splitting not so long ago and a large portion of the electorate remembers more functional government in those days.

Inflation

In the leadup to the election, no issue saw voters from different political parties more united in concern than inflation. In the August Marquette poll, inflation was the top concern for women and seniors; it had fallen slightly by October but remained among their top 3 policy concerns. Forbes reported in October that nearly half of women actively worry about money daily – a higher level than men do.

The pace of inflation is slowing, but the huge increases in the price of necessities have put a heavy strain on family budgets. Voters know that as we go into winter heating season already-high energy costs, and potential further increases will make their budgets even tighter, and seniors will be among the hardest hit.

Voters took these worries into the voting booth.

But they went in with very little input from candidates on their plans to address inflation. Few if any campaigns addressed the issue, and the mainstream media did nothing to press for answers from candidates. In an absence of information, voters who were more concerned about policies than party-line voting were more likely to split their tickets.

Voting based on policy not party might look like this: if they leaned on conventional wisdom that Republicans are more trusted on economic issues and inflation is a national issue, they’d break for Johnson. Then looking down-ticket to the governor’s race they would look to their next priority, education, a state level issue. Evers had focused much of his advertising to highlight his education bona fides so breaking for Evers covered that base.

Public Education

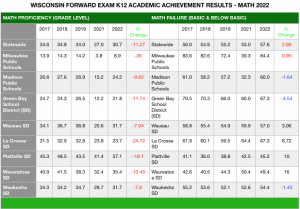

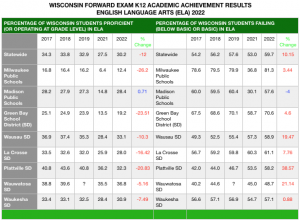

Between CRT, school board election battles, sexualized course content, plummeting achievement scores, unchecked learning loss, increased spending and declining enrollment, and a Department of Public Instruction that stubbornly ignores or defends all of those problems, public education has taken center stage in a much more complex way than the usual spending debate.

Where inflation is perceived as a national issue, education is definitely a state issue. Evers’ background in education, as well as his campaign ads taking credit for phony rankings* showing Wisconsin’s rank going up while test scores go down, provided the only message about education most voters saw.

Crime

We’ve written here, here, here, and here about the huge increase in violent crime, and it has consistently been a top concern for people across the state.

Governor Evers has been loud and proud about his Scold-and-Release views. His Department of Corrections has worked hard to reduce the prison population; he has pardoned over 600 felons giving them gun rights, his parole commission has used their discretion to release hundreds more, and he has refused to remove Milwaukee District Attorney Chisholm from office even though his office’s policies are responsible for increased violence.

Women rated higher levels of concern about crime than men, possibly because they represent 56% of violent crime victims in Wisconsin, while perpetrators are overwhelmingly male. In the August Marquette poll, 94% of women said crime was a concern, compared to 82% of men. In October, 86% of women were concerned, and 83% of men.

Seniors also consistently ranked crime as a higher concern than other age groups. Crime displaced inflation as their top concern in the final Marquette poll, with 93% of seniors expressing concern just days before Election Day.

Crime policy never became the battleground in the gubernatorial race that it did in the U.S. Senate race. The mainstream media, well aware of how important the issue was to voters, never covered many of state and local policy failures that were driving the crime spike, and never demanded answers from candidates. While the gubernatorial candidates had widely differing views on crime, voters didn’t seem to choose based on those views. Perhaps that was because other issues tipped the scales for swing voters.

Our violent crime rate remains high and Milwaukee is on track for yet another increase in homicides in 2022, which probably accounts for 60% of residents there feeling unsafe going about daily activities. Under divided government, we are unlikely to see a change in the status quo. That could prompt voters to revisit the issue in the spring elections as they make choices for DAs, judges, and the Supreme Court seat that’s up where crime is nearly always an issue.

Abortion

There is no doubt the conservative-controlled, progressive-loathed United States Supreme Court delivered Democrats a powerful boost in the form of the Dobbs decision. A large majority of the population supports some level of legalized abortion. Roe allowed elected Republicans to ignore that reality, leaving them ill-prepared to respond to an election-year surprise that pitted them against most of their constituents.

While some political insiders have pointed to abortion as the single issue that turned the red wave pink, the extensive ticket-splitting and high levels of concern among voters about other policy issues suggest that is overly simplistic.

If Roe had stayed intact, the cycle would no doubt have looked different. But as it turned out, in Wisconsin, where the Dobbs decision ended legal abortion, Republicans held one of the most competitive U.S. Senate seats in the nation, picked up a congressional seat, won the state treasurer seat, broadened majorities in both houses of the legislature and came extremely close to taking out the 40-year incumbent Secretary of State and the incumbent Attorney General.

The Democrats credit abortion policy for driving turnout, but the 2022 midterm turnout was actually lower than it was in 2018. Republicans have suggested the issue was a driver for only young women who use abortion as birth control, failing to acknowledge the bigger picture.

The importance of abortion policy grew throughout the cycle. While the level of concern about abortion policy remained steady for men between the August and November Marquette polls, it rose from 4th place to 2nd place for women. Among voters over 60, it rose from 5th place to 4rd. Among the youngest voters 18-29, it moved from 2nd to 1st.

This issue was the subject of much or most of Evers’ TV ads highlighting Michel’s (later-softened) stance, coupled with effective but entirely absurd allegations that Michels tolerated rampant sexual harassment in his company, something the mainstream media failed to fact check and Michels failed to rebut. These sustained, unanswered attacks no doubt had impact on women voters across Wisconsin.

Ironically, the continued split control of state government entrenches the much-referenced 1849 abortion ban. Governor Evers has sworn to veto legislation to provide exceptions for cases of rape or incest, and the Republican legislature will not remove all abortion restrictions. The stalemate will preserve the policy status quo, and abortion policy will doubtless have political ramifications again in 2024.

The People Behind the Pink Wave

A strong case can be made that Wisconsin’s pink wave resulted when a couple of large demographic groups, comprised of higher-than-average propensity voters but often overlooked by the strategist class, didn’t party line vote as expected.

Women voters headed to the polls, not as the two-dimensional-one-issue voters many of the still-mostly-male political strategists on either side suggest, but as managers of family budgets who were concerned about loss of learning and curriculum content, worried about rising violent crime, and, yes, generally opposed to the sudden, complete ban on abortion in the state.

A look at any poll, or a discussion with actual women, makes it clear abortion was not the only thing all women were concerned about, nor was it their top concern. But it was pretty clearly a tiebreaker for women voters faced with choosing between candidates who didn’t win them over on the strength of their other policy positions.

Similarly, senior voters, who interestingly closely tracked with the youngest voters on many issues, were clearly a factor.

Pink Wave Demographics

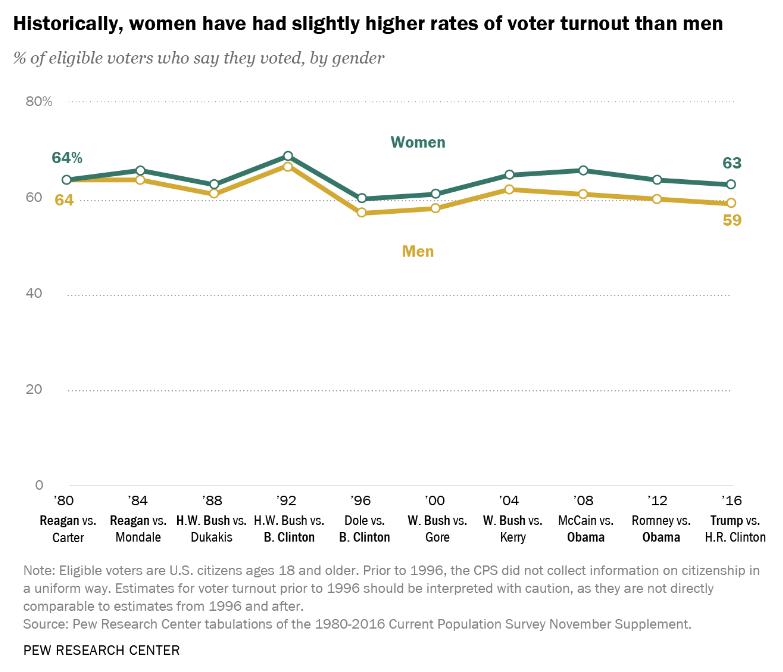

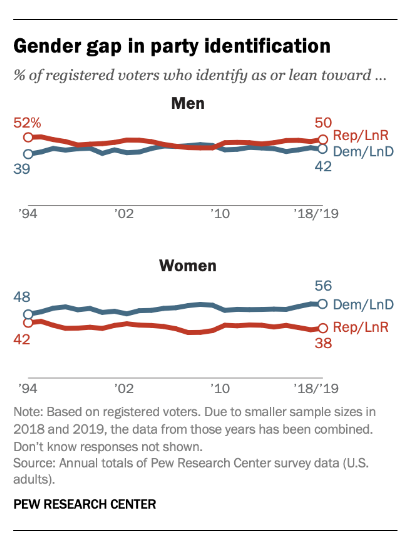

Women represent a larger portion of both the population and the electorate. They vote at higher rates than men, the gap having grown over 4 decades. Women are also more likely to identify as or lean Democratic, although education level, race, ethnicity, and age tend to be stronger indicators of political preference than gender.

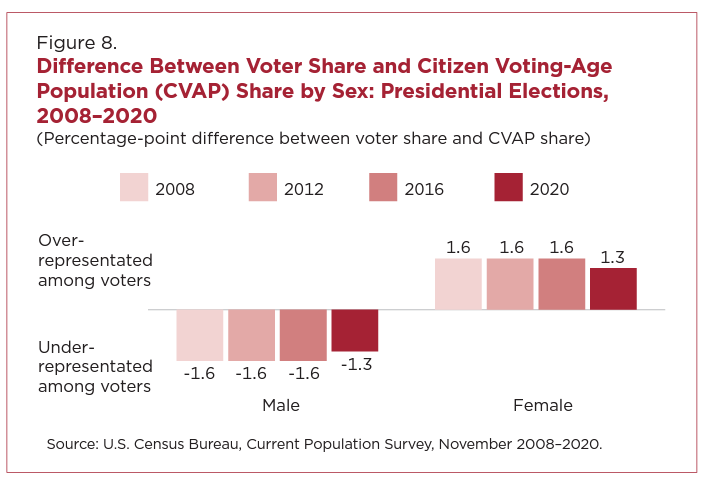

Nationally, the electorate is comprised of roughly 53% women and 47% men. In the 2018 midterms, 55% of women turned out to vote, while 51.8% of men did.

In always high-turnout Wisconsin, 51.4% of voters were women and 48.6% men in the high-turnout 2020 presidential election. A larger portion of a larger group means a larger impact. In a state where winning margins can be razor thin, groups with greater impact would seem more likely to get greater attention.

But the greater impact has not translated into greater attention during campaigns.

When it comes to swaying women voters, the right recognizes women are different than men but doesn’t know what to do about it, while the left doesn’t recognize women as different than men, so they can’t do anything about it. So, both parties look for women candidates (women will vote for other women, right?) and/or they focus on some single “woman’s” issue they figure all women stew over 24/7 (abortion, mammograms, cervical cancer screenings etc.) and assume those concessions are enough to win with women.

It should go without saying – though sadly it cannot – women, like men, vote based on a complex set of priorities, heavily influenced by the positions of candidates on policies that are important to them.

This year may be one of the clearer examples of an election where women changed the outcome. Women went into the ballot box with education and abortion uppermost in their minds, followed by inflation. If education and abortion are state issues, and inflation more national, an Evers/Johnson vote would be the obvious choice for ticket splitters concerned with those issues.

Silver Demographics

The other demographic with potentially outsize impact on elections, and thereby policy, is older voters.

By 2060, the number of seniors in the U.S. will have doubled compared to 2018. In the past decade, Wisconsin has been one of the fastest-aging states, with the population of seniors growing by one-third between 2009 and 2019.

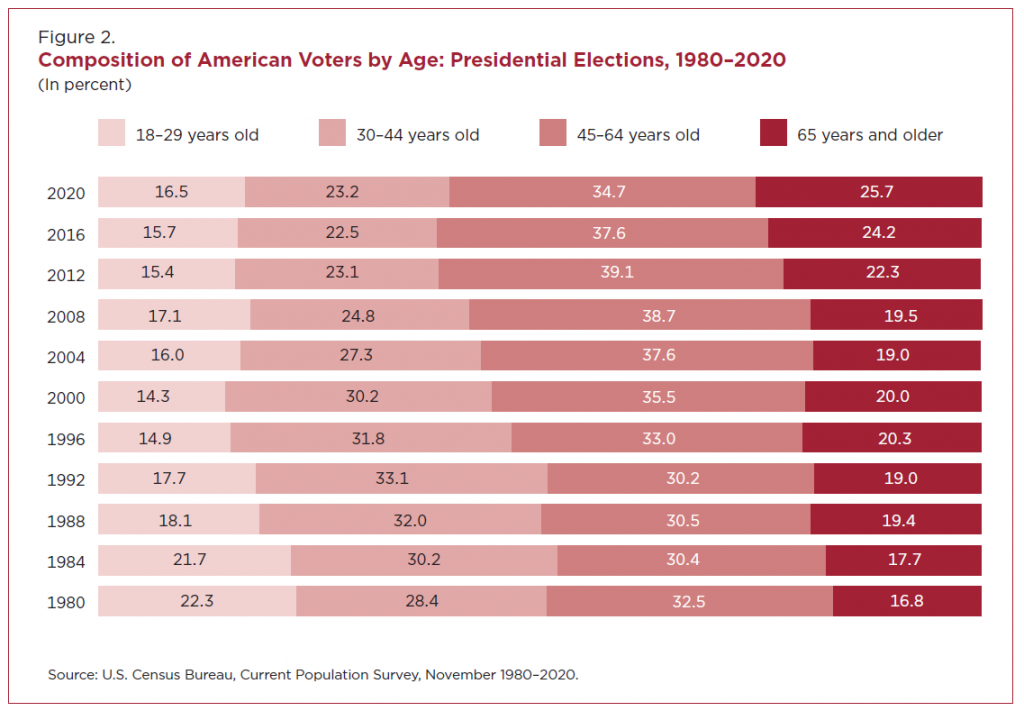

In 1980, voters 65 and over comprised less than 17% of voters. In 2020, they comprised over 25% of the vote while representing only 16% of the population. The “Silver Tsunami” assures this trend will continue to grow.

Seniors have always been voting overachievers, turning out at high levels, and as their numbers grow, their views will carry increasing weight in deciding policy with their votes.

But seniors are another group that’s typically gotten short shrift from campaigns. Generally, they are targeted with a scare tactic about taking away social security or Medicare (shove grandma off that cliff), a line about increasing funding to nursing homes (under 0.04% of the population lives in a nursing home) or promises to cut retirement taxes (40% of seniors rely solely on Social Security, which is untaxed). Political operatives have lost sight of who seniors are and what issues they care about.

The senior population is changing as it grows larger and as people live longer and healthier lives. Some of those changes mean the policies that matter to this group have also changed.

Public education is a concern for seniors, not just because of its impact on property taxes. In 2016, roughly 25% of grandparents 65 and over were caregivers for grandchildren who live with them; at age 85 and over, over 10% of grandparents care for grandchildren who live with them.

Inflation is a greater concern for seniors than ever before, too. The 2019 median household income for seniors was just over $27,000, and about 9% of seniors live in poverty. Most seniors are homeowners, so property taxes certainly matter, but price spikes for groceries, gas, and other necessities have taken a bigger bite out of seniors’ budgets, especially for the 1/3 of senior women who live alone.

And seniors are also more often women. In 2019, among seniors 65 and up, there were 125 women for every 100 senior men; for super-seniors 85 and up, there are 178 women for every 100 men. In predicting a huge red wave, both parties seem to have lost sight of the fact that the youngest seniors, 65-year-old women, were born before the birth control pill was approved in the U.S, and were 16 in 1973 when Roe was decided, at a time when the birth rate for 15–19-year-olds was around 7%. They would remember the U.S. Senate hearings on the safety of the pill, convened by Wisconsin’s Senator Gaylord Nelson.

Even the youngest senior women were adults while the topics of birth control and abortion were at the center of political debate. The final Marquette Law School poll before the election showed the two age groups with the strongest support for legal abortion in the case of rape or incest were 18 to 29-year-olds and those 60 and over. The same was true for opposition to the Dobbs decision.

It seems clear that seniors, particularly women, were motivated by several important issues. Even though well past childbearing years, abortion mattered to seniors, and it didn’t seem that the candidates, particularly but not exclusively on the right, really understood that.

In August, seniors had a negative view of Kleefisch, but were neutral on Michels. By November, half of seniors had an unfavorable view of Michels, over 10 points more unfavorable than any other age group. Evers had a favorable image with seniors. Ron Johnson and Mandela Barnes both had only slightly unfavorable rankings with seniors. Michels’ strikingly high unfavorability with seniors spelled trouble.

President Trump

Political pundits and mainstream media have made much of the impact of former President Trump on last week’s results. Like President Biden, and former President Obama, Trump has some impact in the campaign season – as did former President Obama – candidates seek endorsement from current and former officeholders they believe will help in their races.

Trump is the favorite boogeyman or hero of partisans of both stripes. Democrats point to Trump as the reason for their not-as-bad-as-they-thought performance, while Republicans see him as creating – for better or worse – the realignment of state’s political environment, which they seem to forget began pre-Trump.

For the clear-thinking, it’s hard to make a serious case that, in Wisconsin, where one of the two top-of-ticket, Trump-endorsed Republican candidates ran points above Trump’s 2020 margins in nearly every county, and the other ran points below those same margins, Trump was the major decisive factor – or frankly much of a factor at all.

Consider that Ron Johnson underperformed Trump’s 2020 margin in only 4 counties, by only 1% in each. The inverse was true for Tim Michels, who outperformed Trump in only 4 counties, by only one point in each.

Something was driving ticket-splitters and there’s a clear case that something was a number of policy issues that worried voters across the state and across party lines, and not the former president. Generationally high inflation and violent crime, plummeting student achievement scores, the sudden change to abortion policy were clearly top of mind for voters.

Continuing to see everything thru the lens of Trump shortchanges the people in the state who sent a message that they want to be dealt in on policy, and they will reward candidates who do so.

To end where we began, good policy is good politics. We’ll hear analysis and excuses from the pundits, but the 2022 results were all about people and policy. Voters showed up at the polls and they showed that they care about the issues facing the state. Rehashing failures or successes on data or doors entirely misses the mark.

People and policy matter, and our postmortem of this election made two problems clear:

Campaigns have largely stopped talking to voters about policy, but voters have not stopped caring about policy.

Campaigns are not talking to huge voting blocks – women and seniors among them – about the issues that motivate them in a way that reaches them. In many campaigns, notably on the right, the vast majority of staff are male, and many of the decision-makers are out-of-state, again male, consultants who approach Wisconsin as though it’s just a colder Tennessee. Candidates who do not deal women in on a staff level, and not just as event planners, are engaging in self-harm, shortchanging their campaigns of valuable perspectives and insight into the largest, heaviest-voting segment of the population. We saw some of that play out last week.

Smart policy-makers and aspiring policy-makers will consider the importance of understanding the electorate at a more granular level, and talking to them about the policies they care about.