Is a flat tax worth a sales tax on gas?

A look at the numbers and details of the latest development in Wisconsin’s transportation showdown

May 17, 2017

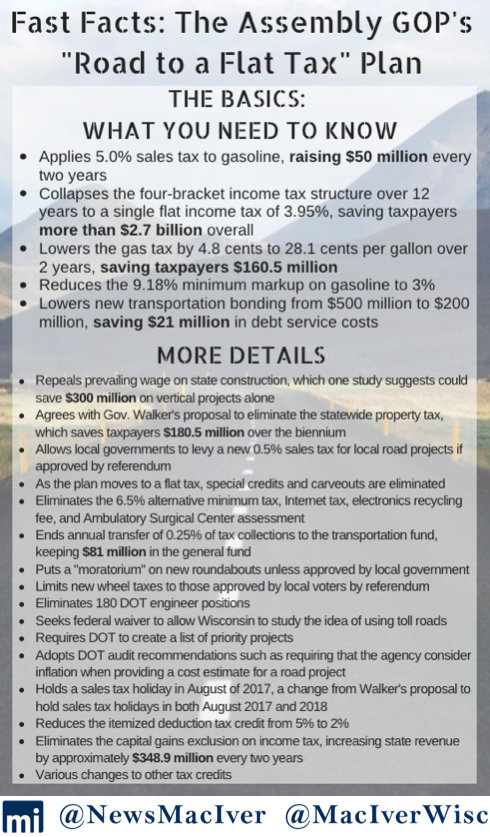

[Madison, Wis…] State Rep. Dale Kooyenga knows the odds are long that his “Road to a Flat Tax” will survive the budget process.The Brookfield Republican’s ambitious transportation and tax reform package aims to build a sustainable transportation infrastructure program while simplifying and lowering the state’s complicated tax code, eventually bringing a 3.95 percent flat income tax to all Wisconsin taxpayers. (For background on what a flat tax could look like in Wisconsin, please read MacIver’s report from January, A Glide Path To A 3% Flat Income Tax).

Kooyenga’s goal of moving away from our highly punitive income tax brackets to a single flat tax is an important goal and one we need to pursue if Wisconsin is to compete for population growth, business start-ups and retiree retention in the future. While Gov. Scott Walker and the Republican-controlled Legislature have provided nearly $5 billion dollars in tax relief since 2011, Wisconsin’s high overall tax ranking has only improved one spot, down to 16th highest among the states.

Ultimately, the proposal could cut taxes by billions of dollars, significantly lowering the burden that has long plagued citizens of this high-tax state. It drives down transportation bonding, potentially saving taxpayers hundreds of millions of dollars in interest payments that could be dedicated to other priorities. The plan also would start to reform Wisconsin’s anti-consumer and unjust minimum markup law, which forces Wisconsinites to pay higher prices on many of the goods they purchase every day. And, if government doesn’t get in the way, Kooyenga’s plan could truly limit the size of state government.

There are big victories for free-market conservatives in this plan; unfortunately, the pros come with one incontrovertible and overriding negative. Kooyenga’s plan, in order to placate the tax-and-spend crowd, makes a deal with the devil: it applies the 5 percent state sales tax, 5.5 percent in almost every county in the state when you add in the local 0.5 percent sales tax option, placing a new tax on a widely-used and critically-important product.

Here is the biggest problem with the proposal to apply the 5 percent sales tax to gas – we would be adding a new tax on a tax, only to be taxed again. It is nearly impossible, as witnessed by the Legislature’s reluctance to agree with Walker’s proposal to abolish the statewide forestry tax, to repeal or get rid of a new tax once it has been created. Most politicians are loathe to ever give up revenue, or as we like to say, your money. Wisconsinites do not need a new tax. Wisconsinites need fewer taxes and an overall lower tax burden.

The transportation proposal does lower the state’s gas tax – at 32.9 cents per gallon one of the highest taxes in the country – by nearly 5 cents. But those savings are overshadowed by the implementation of a new tax that could burrow into the state’s revenue system forever.

Taken separately, there are some very intriguing ideas worth exploring in the reform package. At the top of that list is a flat tax that could not only keep a lot more money in the wallets of Wisconsin taxpayers, it could single-handedly make the Badger State a much more competitive place to do business. States with flat income taxes have better population growth, more in-migration, faster private sector growth, higher personal income growth, and larger gross state project growth than states with high income taxes.

Wisconsin has had a progressive tax structure the entire time it has taxed income, but that doesn’t make the flat tax an “out-there” idea. Seven states levy no individual income tax at all, and eight states have a flat individual income tax, including Illinois, Indiana, and Michigan. Two more states, New Hampshire and Tennessee, only tax income on dividends and interest, and Tennessee is on a glide path to complete elimination of the income tax by 2022.

Some might portray the idea as radical, but it’s important to note that all Illinoisans pay a 3.75 percent flat tax rate. That’s right – millionaires in Chicago pay a lower state income tax rate than single people earning less than $11,000 in Wisconsin.

Wisconsin’s lowest income tax rate of 4 percent is the fourth highest bottom rate among the 33 states with a progressive income tax. Not only do we push away high earners with rates that punish success, we punish the poorest in our society.

Kooyenga’s plan also bolsters the free market by starting to reform the state’s Great Depression-era prevailing wage law, and directly limits the size of government by eliminating 180 state Department of Transportation jobs. It brings “fund integrity” back to the state budget by preventing $81 million from being transferred from the general revenue account to the transportation fund. This is important to those of us who care about GAAP accounting standards.

Kooyenga says there’s been a good deal of misunderstanding, if not misinformation, about his reform package, from its cost to its ultimate impact.

Today, the MacIver Institute takes a closer look at the key elements of the proposal, and what they aim to accomplish.

Numbers Game

Kooyenga these days must feel like a dead man walking. Members of his own party have skewered his proposal, unveiled earlier this month.

Walker has panned the plan as a tax increase at the pump. The Republican governor, pointing to Legislative Fiscal Bureau projections showing a net effect $433 million tax increase, said he cannot support the package.

“To me, that is the most troubling part of the plan,” Walker told the Associated Press. “I think people are taxed enough. I oppose a gas tax increase, no matter what you want to call it.”

While the GOP Assembly made a show of solidarity with Kooyenga during the unveiling of his reform package, several lawmakers tell MacIver News Service the proposal, as it stands, is probably dead on arrival.

Currently, gas is exempted from the 5 percent state sales tax and the 0.5 percent add-on in 64 of Wisconsin’s 72 counties. While Kooyenga justifies the revenue increase with a 4.8 cent-per-gallon reduction in the state’s high gas tax and the lowering of the minimum markup, it doesn’t change the fact that a conservative transportation plan adds a tax.

“The Assembly plan includes a massive net tax increase on fuel to reduce bonding in a budget that has the lowest level of transportation bonding since the 2001-2003 state budget – without any new road projects,” Walker wrote in an email to MacIver News Service. “I am working with members of the Senate and Assembly on reforms that protect taxpayers while investing in our infrastructure – all without an increase on taxes at the pump.”

Transportation bonding may be at its lowest level in 15 years, but debt continues to dog the fund. Assembly Republicans are adamant that the lower bonding level is still just too high.

Walker’s 2017-19 budget proposal includes $6.1 billion for transportation, with $500 million in new bonding.

Kooyenga estimates the sales tax on gas would generate some $660 million in new revenue over the biennium, $300 million of that marked to buy down Walker’s bonding proposal to $200 million. Doing so would significantly ease borrowing costs.

By 2018, the transportation fund is expected to fork out $413 million a year in debt service, representing 22 percent of tax-and-fee dedicated transportation fund revenue. Walker last week reiterated to conservative talk show host Vicki McKenna that state bonding is at its lowest level since 2001-2003.

The Fiscal Bureau projects sales tax collections would be more like $270 million in 2017-18, including $70 million in contingent bonding authority, and $390 million in 2018-19.

Kooyenga and Assembly Republicans have attempted to make debt reduction a huge selling point of the package, but is the current debt load too high? There is disagreement on that front. The Transportation Projects Commission has said the transportation fund could still be considered stable with debt service as high as 25 cents of every transportation dollar.

‘Fund Integrity’

Walker’s budget proposal calls for spending $325 million in general fund money on transportation over the next two years.

Kooyenga notes that what Walker characterized as a $433 million tax increase includes leaving $81 million in the state’s general fund that could no longer be siphoned into the troubled transportation fund. The legislator’s plan puts a lock on the general fund, at least when it comes to transportation.

Walker and fellow Republicans have long criticized his predecessor, Gov. Jim Doyle, a Democrat, for grabbing $1.3 billion from the segregated transportation fund. In November 2014, voters approved a referendum establishing a constitutional amendment ending the practice of raiding the transportation fund for other government programs.

While Kooyenga says he doesn’t find using general fund money for transportation as egregious, he asks, “Why is it right to go from the general fund to transportation but not okay to go from transportation to the general fund?” It’s a matter of fund integrity, the lawmaker says.

Kooyenga’s plan would use the $81 million for income tax reduction. The counties’ portion of the sales tax on gas, an estimated $43 million, would be retained by the state and applied to the flat tax.

Maximum Friction – The Unjust Minimum Markup Law

The reform package rests heavily on reducing Wisconsin’s minimum markup rate from 9.18 percent to 3 percent.

Also known as the Unfair Sales Act, the minimum markup law prohibits the sale of merchandise at less than cost while ratcheting up the “minimum price” for alcohol, tobacco and gasoline.

Any move by lawmakers to reform this special interest protection will be difficult. There will be pitched resistance from an army of lobbyists and flacks who will stop at nothing to maintain the status quo.

Krist Atanasoff, owner of Iron River, Mich.-based Krist Oil Co. and an outspoken critic of the minimum markup law, operates 37 gas stations in Wisconsin and 36 in Michigan. Although Michigan’s gas tax is 5 cents higher than Wisconsin’s, Atanasoff says his Wisconsin customers pay a higher price at the pump thanks to the state’s “dumb state law.” The businessman supports Kooyenga’s plan.

“As a petroleum marketer, I don’t want the crony capitalist protections so many in our industry want. I just want to compete, without government favor,” Atanasoff wrote this week in a letter endorsing “The Road to a Flat Tax.” As the convenience store chain owner notes, none of the money consumers pay in minimum markup costs goes to road construction or upkeep. “It is merely a government-mandated guaranteed profit margin for one industry.”

But are there any guarantees that consumers will see cost savings at the pump should the minimum markup rate be reduced? No. Some speculate that convenience stores could simply raise the price of gas to offset the loss.

Matt Hauser, executive director of the Petroleum Marketers, told the Wisconsin Radio Network that there has never been conclusive evidence changing or eliminating the markup on gas would offset a tax increase. He, again, defended the minimum markup law as protection from large chain retailers pricing out smaller operators.

“We’re concerned it’s really just a smoke screen to draw away from the real issue…that Wisconsin is getting ready to implement a significant tax increase on gasoline,” Hauser told WRN, referring to Kooyenga’s plan to lift the sales tax exemption on gas.

Kooyenga countered that it’s the convenience store lobby creating the smoke screen. The minimum markup is applied on top of the state’s gas tax. Lowering the tax by nearly 5 cents would cut into gas station profits.

While the Legislative Fiscal Bureau examined the other elements of Kooyenga’s reform package, it curiously seems to have taken a pass on reviewing the minimum markup reduction and the impact it would have on consumers.

The mark down on minimum markup is a small step in the right direction but a colossal missed opportunity. What about all of the other products consumers are overcharged on because the minimum markup is applied? Why is it the job of the state government to prevent businesses from giving their customers a better deal or a low, low price?

The minimum markup law is an unjust law. Wisconsin consumers are being ripped off everyday and every time a business is prevented from offering their products at the lowest price possible. But making an unjust law a few percentage points better does not suddenly make it a just law.

Mega Money

Wisconsin’s powerful road-building lobby has offered a relatively tepid response to Kooyenga’s proposal – no sharp criticisms, but certainly no ringing endorsements. Road builders, of course, want more money now, but they like the projected $3 billion in new revenue that could be generated over the 12-year life of the transportation/tax plan. That money could be used to buy down debt, but it more than likely would go to projects.

The Southeast Wisconsin Mega Projects, north and south and eventually east and west, are pegged at $9 billion-plus.

Assembly Speaker Robin Vos (R-Rochester) and Rep. John Nygren (R-Marinette), who serves as co-chairman of the Legislature’s budget-writing Joint Finance Committee, have sought much more in revenue. They have long said every idea is on the table, including higher gas taxes and vehicle fees, but they insist Kooyenga’s reform package is a good start in finding long-term solutions for Wisconsin’s transportation budget problems.

One of the big complaints from fiscal conservatives is that the plan includes an increase in funding for a Wisconsin Department of Transportation that has been found to be poor stewards of taxpayer money. An audit released earlier this year showed the agency was riddled with significant cost overruns, due in large part to its failure to account for inflation on major highway projects.

“I’m not giving DOT an additional cent,” Kooyenga said. “I’m actually giving DOT less money because I’m cutting 180 of their engineers. I am lowering bonding.” Kooyenga, a certified public accountant who helped uncover a huge surplus in the poverty-declaring University of Wisconsin System, does not consider bonding – or using tax money to pay down tax money – as increased revenue for the agency.

Checking Government Growth – Lowering Tax Revenues to Control the Growth of Government

Kooyenga’s reform package, he says, limits the growth of state government. The proposal’s most ambitious and quite frankly most appealing idea, a 3.95 percent flat tax phased-in over 12 years, could slow government growth.

“We are reducing the size of government by $2.3 billion that never gets here,” Kooyenga said. “This represents about 1.5 percent growth that will not go to increasing the size of government. It will stay in income taxpayers’ pockets.”

The tax cuts are even higher than Kooyenga’s projections, according to a Fiscal Bureau review. The flat tax would trim income taxes by a net $2.7 billion by 2029, the bureau reported Wednesday. Democrats and their friends on the left are characterizing Kooyenga’s plan as tax cuts for the wealthy, with a little over one-third of the reductions targeted for taxpayers making $300,000-plus per year.

“The simplicity of the flat tax masks the inequality of it,” Rep. Gordon Hintz (D-Oshkosh) told the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. “It’s really a tax giveaway to the wealthiest individuals.”

Or as we like to point out, a flat tax is really about tax fairness and stopping the counterproductive punishment of success. Simple math shows that Hintz is just plain wrong. A person earning $25,000 a year will pay $1,000 in tax under a 4 percent flat tax system. A person making $300,000 a year will pay $12,000 in tax.

The successful will still pay more taxes to cover the cost of government under a flat tax system but it would no longer be at an unfair and inequitable ascending rate.

Critics of a flat tax also don’t recognize the significance of the individual income tax in today’s economy – particularly for pass-through businesses. Business structures have changed quite a bit since the invention of the Internet, let alone since the invention of the income tax.

Pass-through businesses – including S-corps, sole proprietorships, and partnerships – are an increasingly common form of business practice in which profits are taxed under the individual income tax rather than the corporate tax. More than half of working Wisconsinites are employed by a pass-through business, which pay a top marginal income tax rate of more than 48 percent – the eighth highest rate in the country.

Ultimately, Kooyenga and advocates of a flat tax say the reform is about fairness, lifting the yoke of heavy taxation off of all taxpayers. Wisconsin has long had its progressive tax code under the guise of being more fair and friendly to the poor. Liberals in particular demand the rich must “pay their fair share” and help reduce income inequality by paying more in taxes.

Quantitative state data from 2002 to 2012 show states with flat income taxes have better population growth, more in-migration, faster private sector growth, higher personal income growth, and larger gross state product than states with high income taxes. State revenue also grew more in states with no income taxes, showing that life doesn’t grind to a halt when the government stops taxing its citizens as heavily.

As the MacIver Institute notes in its “Glide Path To A 3% Flat Tax Income Tax,” tax migration plays a significant role in economic competitiveness.

“Wisconsin’s reputation as a high-tax state has a significant impact on the state’s ability not only to attract newcomers, but also to retain those who are already residents,” MacIver’s Ola Lisowski wrote in a January policy brief. “Annually, Wisconsin loses an estimated $136 million in adjusted gross income to tax migration.”

Census Bureau data show that the majority of those leaving Wisconsin are heading to states that boast warmer weather and lower taxes, such as Florida, Arizona, Texas, and Colorado. A flat tax could stem the tide of Wisconsinites fleeing the state for lower tax burdens.

Some conservative lawmakers have expressed concerns that a change in political leadership could wipe out the flat tax. Kooyenga says it would take a two-thirds vote in both houses to change the rates once they are in statute. The beautiful thing about it all, the lawmaker says, is that the income tax cuts would go on, no matter who’s in office. “It’s on autopilot.”

Rounding Down

While making up a fraction of the traffic control systems statewide, not many transportation topics have ignited more controversy than roundabouts. Beyond their costs, critics say roundabouts pop up without much DOT consideration of public input.

Kooyenga’s reform package would prohibit DOT and local governments from designing a roundabout for any state or local highway unless the roundabout is approved by the local government of the community where the roundabout would be located. But the moratorium would be in place for just two years and would not apply to projects that commenced before the moratorium bill is signed.

Taxpayer Option

The transportation plan would allow counties to impose a 0.5 percent sales tax, with the proceeds to be used for local road maintenance and repair. Voters must approve the local roads optional sales tax at referendum. The ballot question must be held during a spring election or a general election, not during the lower voter turnout elections. The sales tax would be in effect for four years, with a four-year renewal, if voters concur. If voters reject the question, the county would have to wait at least 12 months before putting the issue on the ballot. It all goes away after Dec. 31, 2027. Local governments in the county would divide 50 percent of annual proceeds for their road repair and maintenance needs.

The optional sales tax would come with a “maintenance of effort” provision. Such mandates under Obamacare have tied states’ hands and extended financial obligations under the law. They lock governments into maintaining taxpayer-funded programs, typically at an escalating cost to taxpayers.

Republican governors have long railed against the extension of the maintenance-of-effort imposed in the “free” money to states in the 2009 federal stimulus package. States were forbidden to make major changes in Medicaid eligibility. “Therefore, Medicaid spending has continued to rise as lawmakers have chosen to cut other programs or raise taxes,” wrote John Hood in a 2012 National Review piece headlined, “Say No To Medicaid Expansion.”

Kooyenga says the idea behind his maintenance-of-effort mandate in his local option sales tax proposal is to keep local governments from shifting sales-tax-based transportation money into another government fund. But those who warned against Medicaid expansion have seen their admonitions come to pass. The base of Medicaid spending, once expanded, continues to grow at a broader, expanded rate.

The transportation plan includes the complete repeal of the state’s prevailing wage law, an anti-free-market giveaway to labor unions at the expense of taxpayers. The law requires wages on taxpayer-funded construction projects to be paid at inflated rates preferred by unions. Two years ago, the Republican-controlled Legislature repealed prevailing wages for certain local projects. If only conservatives had control of every branch of the federal government so we could make some progress with the equally repugnant Davis-Bacon Act.

Kooyenga’s reform package adopts many of the cost-savings and oversight recommendations included in the Legislative Audit Bureau’s January report.

The Final Analysis

While they may not support his proposal, or at least elements of it, many of Kooyenga’s Republican colleagues say the lawmaker did what Republican leadership said the party would do after posting historic wins in November: Go big and bold. He was charged with a Herculean task in coming up with a plan that would solve the DOT’s budget problems, put Wisconsin on the road to real income tax reduction, and work to bring a broad spectrum of competing interests to some kind of consensus.

“I understand there is an insatiable appetite” for transportation money, Kooyenga said. “I just thought it was my job to figure out what we need and go from there.”

While it includes some worthwhile, free-market ideas, Kooyenga’s reform proposal ultimately is flawed by its need to appease. It has the fingerprints of politics and special interests all over it. Anytime politicians make a decision based on politics or the next election, taxpayers lose.

While proponents claim the gasoline sales tax is not a tax increase but simply an expansion of the tax base, we disagree. There’s no way around it – this is a tax increase for the consumer.

According to the nonpartisan Legislative Fiscal Bureau, the sales tax would result in an equivalent fuel tax increase of 7.2 cents per gallon for gas and 10 cents for diesel, based on a price of $2.40 per gallon of gas and $2.95 per gallon of diesel. The pain at the pump only increases as the price per gallon of gas increases. What happens when gas prices hit $3.50 per gallon again? What about $4? Kooyenga has said the idea is to put curbs on high-end and low-end pricing, but consumers have a right to be concerned.

While we applaud the immediate 4.8-cent cut in the gas tax, without scoring the impact of the change in the minimum markup law, questions remain about the overall taxpayer impact of the transportation funding plan. We would be much more comfortable with the overall design of this proposal if it deleted the entire minimum markup law and let full competition for customers drive down the price of gas. MacIver has spent a great amount of time and effort reporting on the consumer injustice that is Wisconsin’s minimum markup law. Our feelings are clear. Why does the government have any role in the setting of prices? Sounds like a scheme you might find in Venezuela.

When it comes to taxation, simplicity and transparency are critical to a fair and effective tax system. Having state government impose a sales tax on top of a tax is a step in the wrong direction.

In the final analysis the question remains: Is a simplified, fairer flat tax worth the price of applying the sales tax to gasoline? We think not. While there is much to like in “The Road to a Flat Tax,” there is more work needed to make it a good deal for taxpayers.