Dan O’Donnell destroys the arguments for ranked-choice voting; an overly complicated, unconstitutional mess of an electoral system.

Dec. 13, 2023

Perspective by Dan O’DOnnell

You know what the problem is with voting? It’s just too easy. You fill in the circle next to the candidate you like best, and then you turn in your ballot. A few hours later, you find out if your candidate won. I mean, come on, what is that? There should be at least five or six candidates for whom you must vote, and you should have to wait a month for the results!

Has anyone, anywhere, in the history of democracy ever uttered the above paragraph? Only the supporters of the needlessly complicated morass known as ranked-choice voting. On Tuesday, a bipartisan group of Wisconsin legislators held a Senate hearing aimed at convincing the gullible that replacing the “one person, one vote” standard set forth in the Constitution with a system so labyrinthine that its results often aren’t known for weeks.

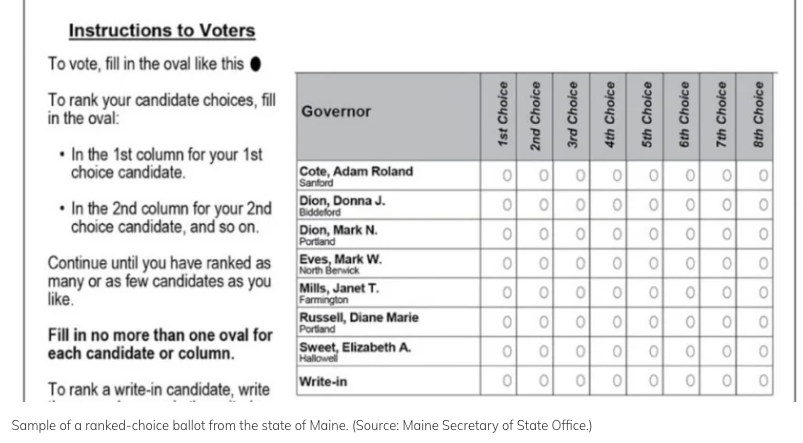

Ranked-choice voting, which has taken hold in the far-left bastions of Hawaii, Maine, and New York City and even the otherwise sane Alaska, eliminates partisan primaries and forces voters to rank candidates in order of preference (usually from first to fifth). If a candidate gets more than 50 percent of the vote (a near impossibility with so many candidates on the ballot), then that candidate is declared the winner. If a candidate doesn’t get more than 50 percent, then things get insane.

The votes are counted and the candidate who is ranked first on the fewest number of ballots) is eliminated. The ballots that featured the eliminated candidate as the first choice are then recounted and each voter’s second choice is elevated to first and votes are awarded to the remaining candidates accordingly. The process is then repeated until only one candidate gets more than 50 percent of the vote.

As you might imagine, this is an incredibly time-consuming and labor-intensive process which is prone to near-constant error. Voters in New York City waited nearly a month in 2021 for the results of their mayoral primary election, while a school board race in Alameda County, California was upended in late 2022 when a tabulation mistake led to the wrong candidate being declared the winner (the third-place finisher actually won).

The process of counting and recounting ballots in secret over the course of days or even weeks naturally breeds suspicion, and Alameda County’s nightmare should prove instructive, as the mistake wasn’t discovered for more than a month and the election’s rightful winner was very nearly cheated out of a seat. This is not to suggest that anything nefarious was at work, but the complexity of the ranked-choice voting system makes it extremely vulnerable to bad actors. If very few people understand how the votes are counted and far fewer have the means or the time to double-check the count, then election oversight is impossible and faith in the electoral process is hopelessly eroded.

The system was so disastrous that one of its earliest adopters, Pierce County, Washington, abandoned it just four years after implementing it…but not before spending a whopping $1.6 million on it during the 2008 election cycle.

Ranked-choice voting isn’t just expensive; it also disenfranchises voters when their ballots are “exhausted” and then ultimately thrown out. In a ranked-choice election with five candidates, voters must rank each of the five. But what happens if they don’t? What if they just rank two or three? Say a voter ranks just two of five candidates because he doesn’t like any of the other three and can’t bring himself to put a check next to any of them. In the first round of voting, his candidate finishes last and is eliminated. In the second round of voting, his second choice becomes his first. If that candidate finishes last, then the voter’s ballot is exhausted. In the third round of voting, it is simply thrown out and not counted. That voter essentially doesn’t get a say in who ultimately wins the election because his votes stopped counting after the second round.

In Alaska’s congressional election last year, there were three candidates: Republicans Sarah Palin and Nick Begich III and Democrat Mary Peltola. Alaska is an overwhelmingly Republican state that voted for Donald Trump by 10 percentage points over Joe Biden in 2020 and voted for Trump over Hillary Clinton by 15 points in 2016. Somehow, though, it also elected a Democrat, Peltola to Congress in 2022.

How? Exhausted ballots in a ranked-choice election. In the first round of counting, Republicans Palin and Begich received a combined 60 percent of the vote. But thousands of Republican voters either refused to put a mark next to the Democrat Peltola’s name or didn’t know their ballots might be eventually discarded if they didn’t, so nearly 15,000 votes were exhausted after two rounds and Peltola won by just 5,000 votes.

Does that sound like the will of the people was fulfilled? Clearly, Alaskans overwhelmingly wanted a Republican to represent them but because of ranked-choice voting (and only because of ranked-choice voting), they are represented by a Democrat. 15,000 Alaskans essentially had no say in the matter simply because they wouldn’t vote for a candidate whom they didn’t like.

A nearly identical situation happened in Maine four years earlier, too. After the first round of voting, Republican Congressional candidate Bruce Polquin led Democat Jared Golden 46.3 percent to 45.6 percent. Because a significant number of Polquin’s voters refused to rank Golden, 8,000 ballots were exhausted and thus thrown out and Golden won the election with fewer than half of the total ballots cast ultimately being counted in the final tally.

Herein lies the fatal flaw of ranked-choice voting: It unconstitutionally eliminates the Constitution’s “one person, one vote” doctrine. Consider the Trump-Biden election of 2020: A voter chooses either Trump or Biden or any of the other minor party candidates and her vote is counted once in the total for the candidate she chooses. Not so in ranked-choice voting. If a voter refuses to rank each of those minor party candidates or, say, hates Biden so much that she just can’t bring herself to rank him at all, she runs the very real risk of her vote not counting at all.

Moreover, a voter who ranks every single candidate will have a ballot that registers more votes than another. Ballots that are not exhausted are counted more times than ballots that are exhausted in ranked-choice voting; ergo one person has more “votes” than another.

The concept of a second choice counting as the first is itself a violation of “one person, one vote” and it often results in a voter casting a ballot for a candidate that he or she never intended to vote for. Let’s say a 2020 voter listed Trump first and Biden fourth out of five candidates but Trump was eliminated on the fourth round of voting. If the final round came down to Biden and the candidate that voter listed fifth, Biden would be awarded that voter’s vote. That voter would contribute to Biden’s victory even though he wanted Trump to be his President.

The cynic would suggest that this is the point: To use ranked-choice voting to elect candidates whom a majority of the public rejects (as in Alaska in 2022 and Maine in 2018). Regardless of the outcome of ranked-choice elections, though, the system is far too unwieldy and susceptible to error to be effective. There is a reason, for instance, that New York City only uses ranked-choice for its mayoral primary and not its general election. The tabulation of that many ballots might actually take a year to complete, and the legal challenges might ensure that a winner isn’t declared until it’s time for the next mayoral election.

As if the logistics of ranked-choice voting weren’t enough to scare away policymakers, the blatant unconstitutionality of a system that allows one person to cast multiple votes and ballots to be thrown out (thereby disenfranchising untold numbers of voters) should.

Ranked-choice is a disaster and should be rejected the second it is proposed. Or, better yet, the decision on whether it should be implemented should be put to a ranked-choice vote. At least then it will take a few years before anyone knows what the results are.