Wisconsin English Language Arts Standards Were Changed During the Pandemic

DPI Program Highlights Black English as a Separate Language

Presenter Claims Current Teaching of English to Black Students is an Act of Curriculum Violence

During recent budget cycles there’s been a greater focus on funding for disabled students. Last budget the level of funding was increased $86 million and the previous budget saw an increase of about $80 million which according to advocates is woefully inadequate. One of the reasons for these increases has been the perceived underfunding of programs for disabled students in public schools, in large part because the federal government has fallen short of promised funding levels. It’s also in part due to the dramatically increasing numbers of children receiving special education services; nationally those students now make up 15% of the total public school enrollment.

The federal government does send the state Department of Public Instruction specific funding for disabled student programming that DPI passes through to an organization called The Network, which we’ve written about before here, here and here. With the needs what they are, it seems like The Network would be judiciously directing the funds to help disabled students.

That’s not quite how it works out. The Network uses those dollars to conduct seminars that largely focus on perceived racism and white supremacy in education.

Black Linguistic Justice

Earlier this year, The Network’s Winter 2023 program – a seminar developed with DPI for hundreds of Wisconsin teachers and others in the education establishment – featured a presentation entitled “What It Look Like: Becoming (and Supporting) Arbiters of Black Linguistic Justice.” This session was presented by Teaira McMurtry, a speaker from Wisconsin, educated in Wisconsin (BA Parkside, MA Alverno, PhD Cardinal Stritch), who worked in Milwaukee Public Schools as a teacher and district administrator for 12 years. McMurtry now teaches Education students at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and believes we should have Black Language in all classrooms.

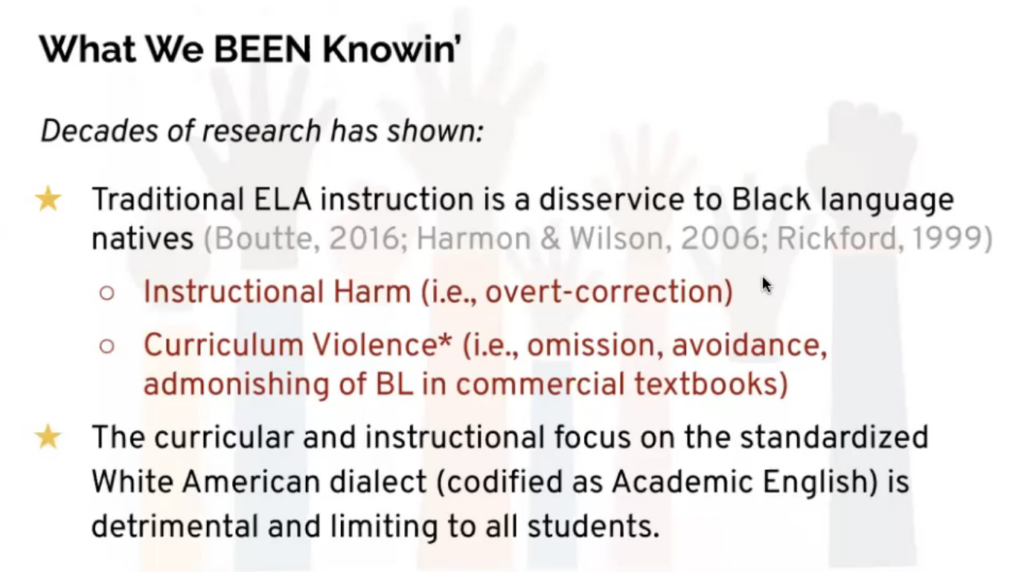

McMurtry characterizes the use of traditional ELA instruction as an act of “curriculum violence” that causes instructional harm. Violence and harm, done to Black students simply through the teaching of Standard English.

But, she says, these harms can be ameliorated by embracing the use and teaching of Black English (BE), as a separate language, to achieve justice for its speakers.

Fundamentals of Black English

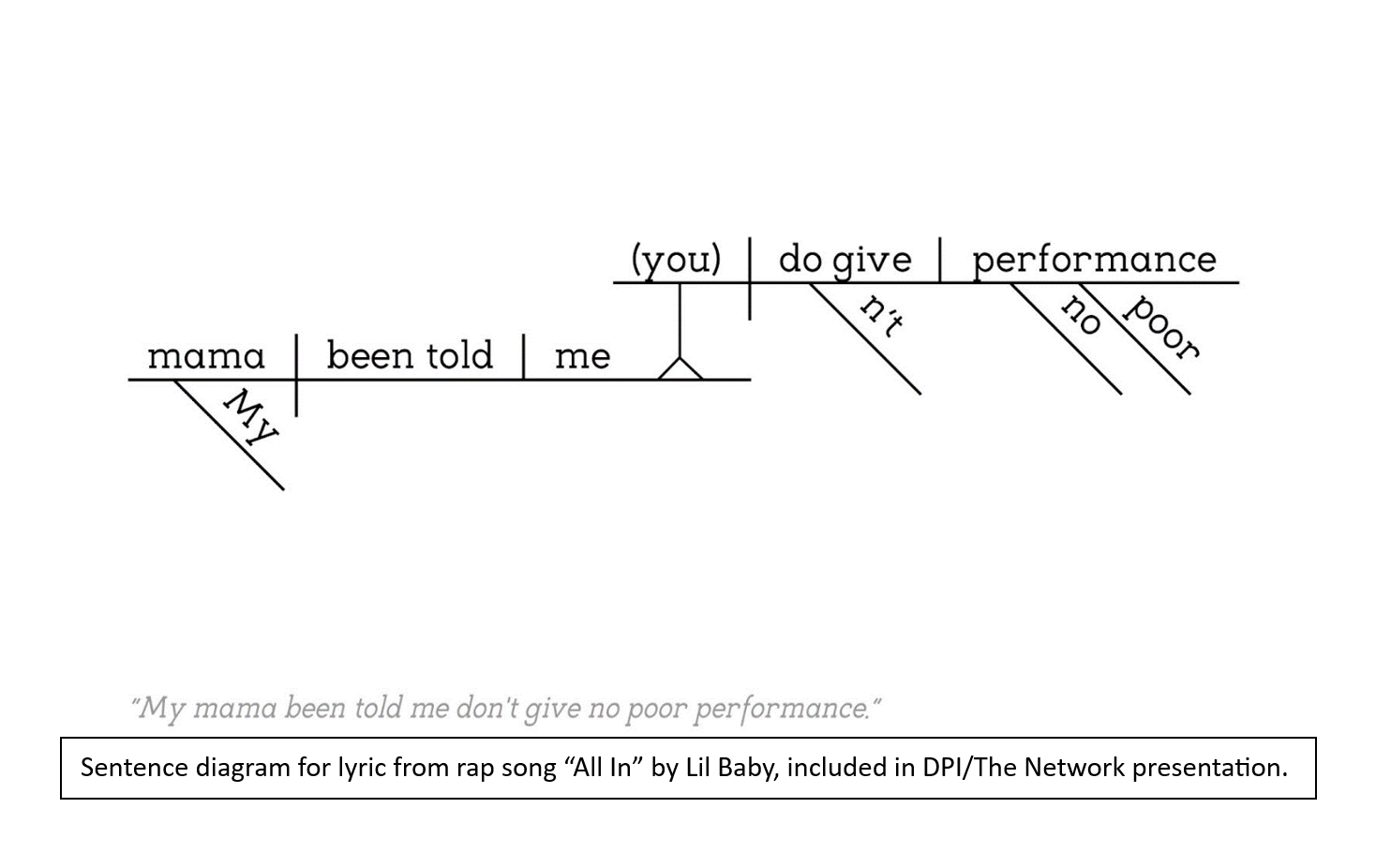

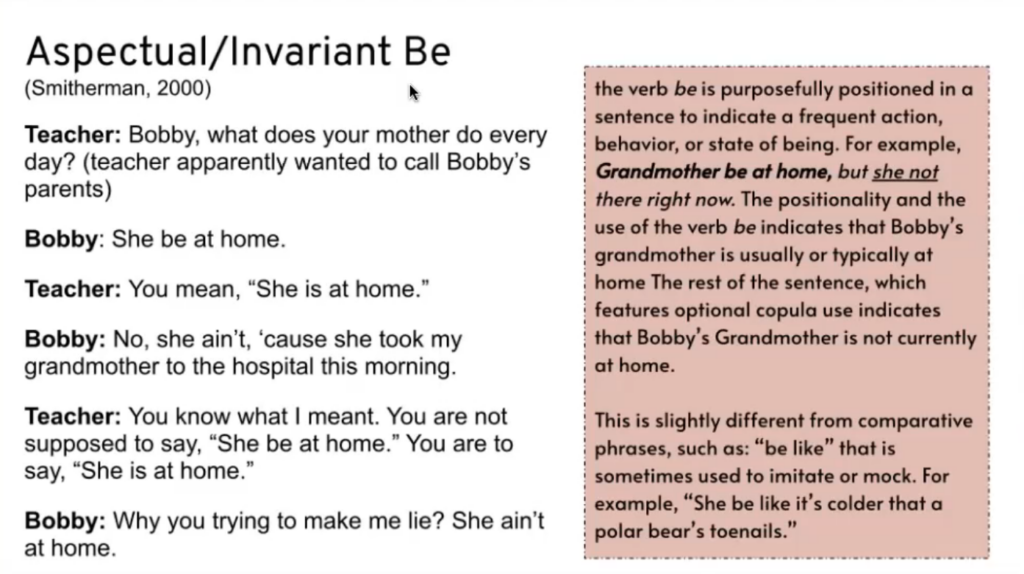

McMurtry highlighted an example (see below) of a characteristic of Black English that many non-Black English speakers might see as incorrect usage, when viewed through the lens of the racist codification of Standard English (SE). Standard English, also called Academic English or Mainstream English, follows spelling, grammar, pronunciation and punctuation rules, is generally uniform, and is traditionally taught in schools. The children speaking BE are speaking correctly, using proper grammar, in their own language, the language of their ancestors. Being corrected as though they are wrong to do so, and required instead to use SE, is harmful to their learning and racist.

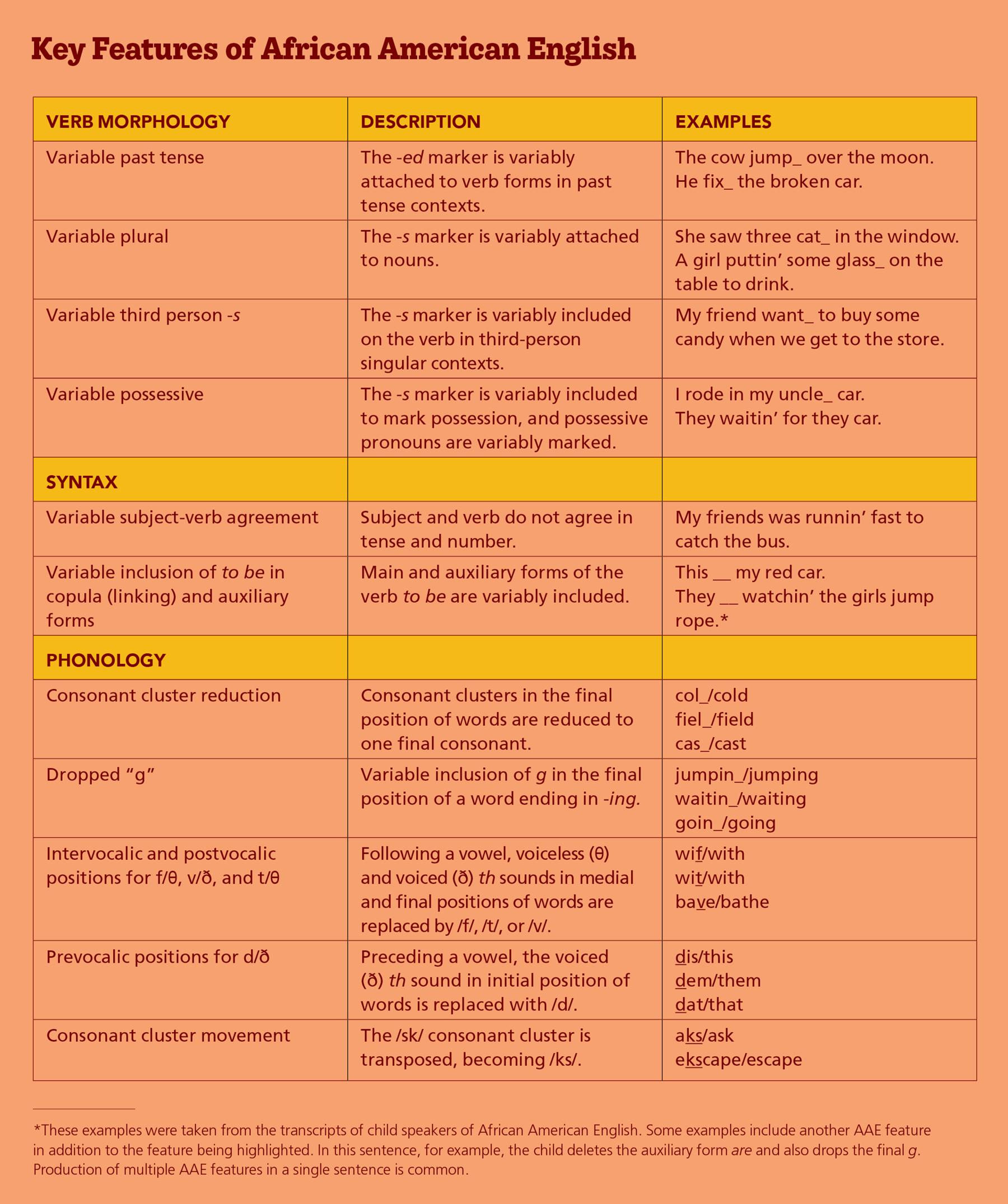

McMurtry is not alone in the assertion that young BE speakers are disadvantaged by having to learn and speak a language at school that differs from what is spoken in their homes. A recent article published in the American Educator, co-authored by UW-Madison professor Mark Seidenberg, contains this chart detailing explaining more key features of BE. The article also claims pushing Black students to learn Standard English is responsible for low test scores, reading delays and emotional pain.

Wisconsin’s Updated ELA Standards: Written to Codify Anti-Racist Teaching

But McMurtry expressed how Wisconsin is uniquely positioned as a trendsetter based on our new ELA standards adopted in 2020 by then-DPI Superintendent Carolyn Stanford Taylor. The process of revising standards is led by a large group of teachers and stakeholders, with public feedback, and signed off on by the DPI Superintendent. McMurtry was a member the team that developed the standards, so she’s well-placed to opine on how they were written and what they were intended to do.

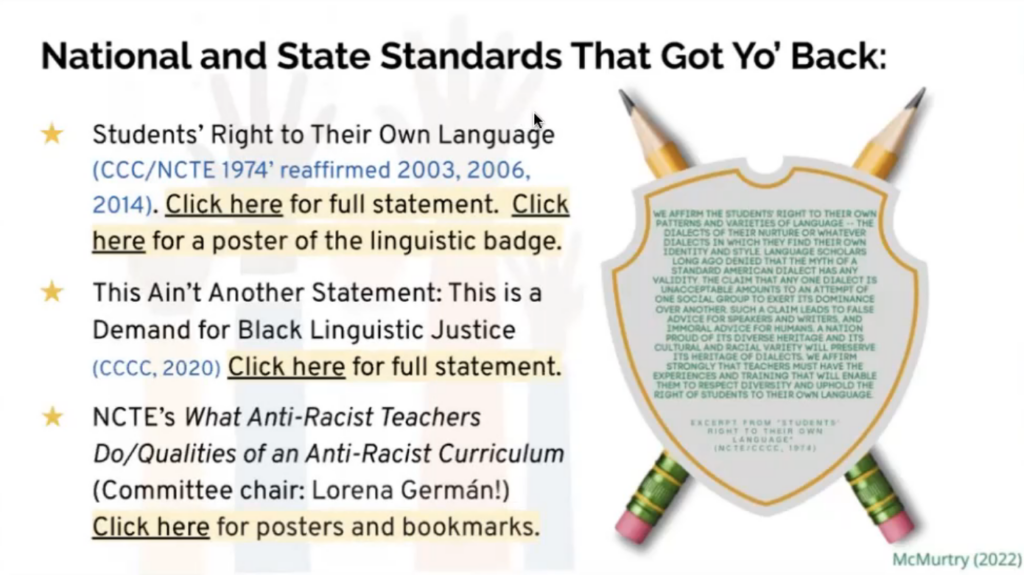

And what McMurtry says is that national standards provide students with the right to use their own language in formal academic writing and Wisconsin’s newly revised ELA standards – in what she calls a huge shift – now call for ELA2 which she defines as language instruction that is artful and anti-racist.

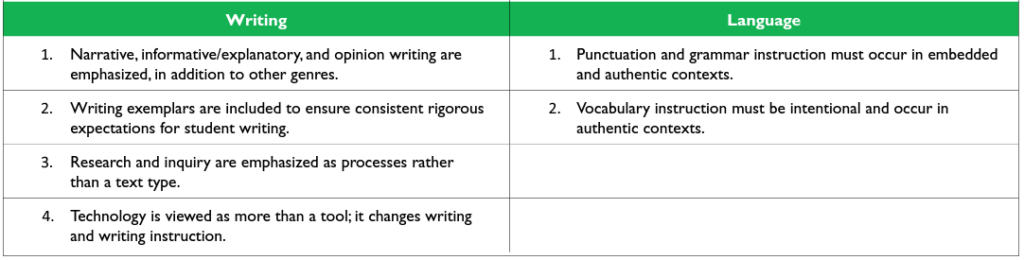

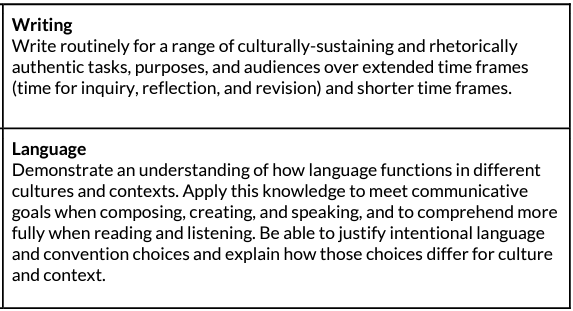

DPI’s 2020 revised standards document indicates the 2010 standard focused on reading and writing, while the new standards emphasize the “variety and complexity of language experiences.” These charts from both those documents bear out a markedly differing approach.

2010 Wisconsin Standards: Emphases of ELA in Writing and Language:

2020 Wisconsin Standards: Overarching Statements in Writing and Language:

The 2021 and 2020 standards are on common ground in both asserting “literacy is an evolving concept” which provides a bit of context to abysmal proficiency scores – it’s difficult to teach something that can’t be defined and even harder to hold educators responsible for not achieving a moving target. But McMurtry encouraged the teachers in her audience to read the standards critically to see what they “don’t say” as they consider curriculum. A look at the side-by-side comparison of the changes between the 2010 and 2020 standards shows it’s also important to look at what they do say.

More Culture and Identity, Less Linguistic Precision

For example, beginning in Kindergarten and for every grade, the new standards look for students to understand where it’s “appropriate” to use standardized English. (In 2010 it was assumed that standardized English was always appropriate in study.) Under the 2020 standards, Kindergarteners (with guidance and support) should compose text with “culturally-sustaining” development and organization. They also should be taught to recognize and appreciate linguistic diversity in the school community.

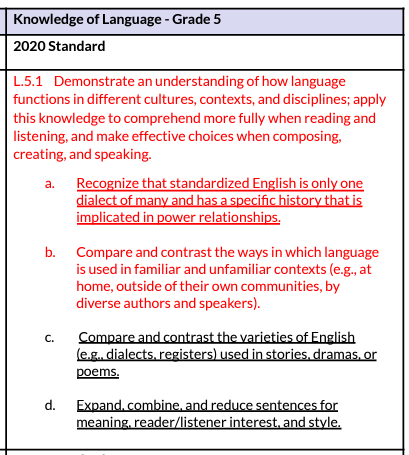

Under the new standards, 5th graders on upwards should learn to “Recognize that standardized English is only one dialect of many and has a specific history that is implicated in power relationships.”

In Grade 8 students must analyze possible biases in literary texts. In Grade 10, the 2010 standard that called for using precise words and phrases was removed and replaced with use of “culturally-sustaining” word choices. In Grades 11 and 12, students now must explain how an author’s identity and culture affect perspective.

Removed From Wisconsin’s 2020 Standards: The Preamble and Shakespeare

A variation of the word ‘culture’ (e.g. cultural) was added more than 60 times. The words ‘identity,’ ‘representation,’ and ‘diversity’ were added roughly a dozen times each. Removed from the standards were The Preamble to the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, The Federalist, Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address, Shakespeare, myths, and most references to precise word choice.

In the selection below, the red text is new to the 2020 standards:

Demanding Black Linguistic Justice

In 2020 McMurtry coauthored the “Demand for Black Linguistic Justice” with other members of the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) and their constituent group the Conference on College Composition and Communication (CCCC). They assert Black language is devalued in schools, reflecting Black lives being devalued in the world; anti-Black linguistic racism is used to diminish Black students, reflecting deliberate anti-Black racism and violence inflicted on Blacks.

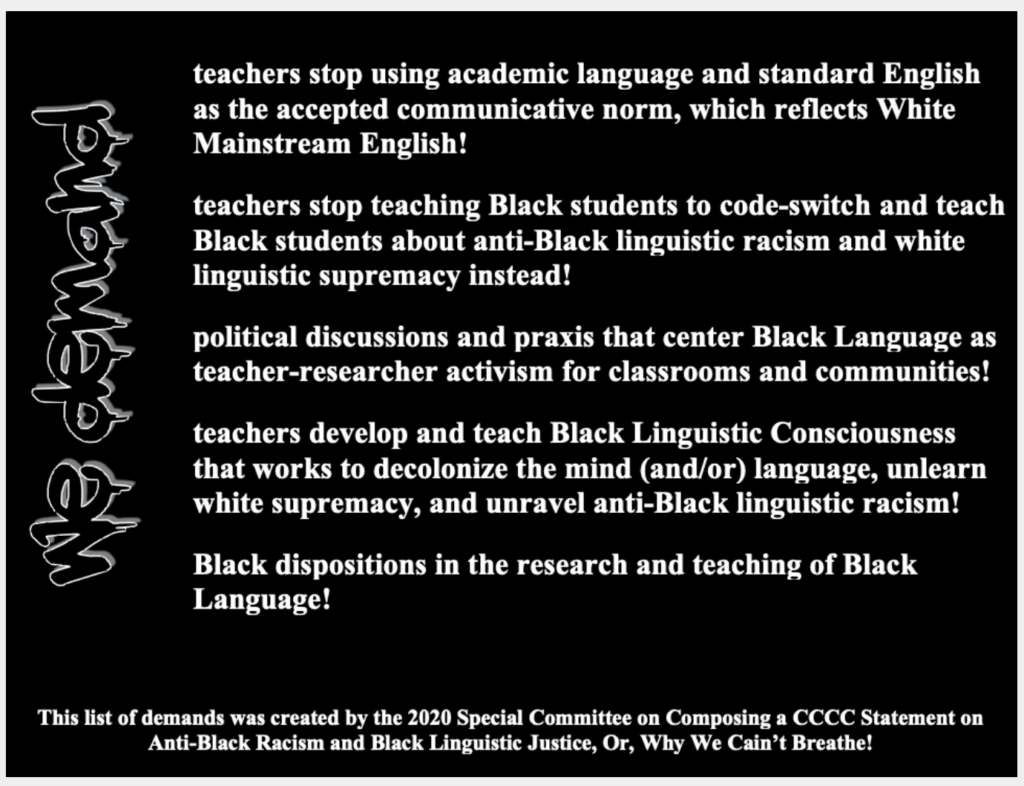

In response to those concerns they issued this list of demands; some of them are now enabled and required by the current Wisconsin standards:

Each of the main demands are backed by several specific sub-demands including:

- Ending the use of Academic English or Standard English which are “notions of white supremacy” and contribute to anti-Black linguistic racism.

- Instituting classroom political discussions – guided by teacher-researcher-activists – about those who seek to annihilate Black language and life.

- Banning of race-neutral words when discussing Black English, including multilingualism, translingualism, linguistic diversity.

- Decolonizing minds of teachers.

- Ending Black linguistic appropriation.

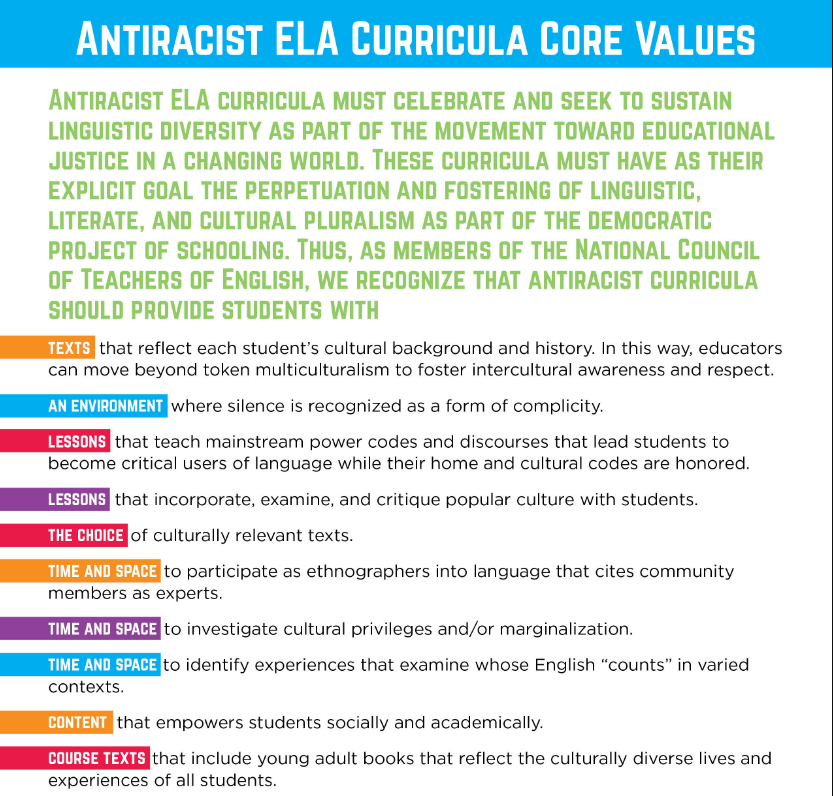

McMurtry also highlighted other NCTE work demonstrating how racism embedded in English Language Instruction (ELA) must be replaced by anti-racist ELA instruction. Characteristics of anti-racist English teaching include providing students things like:

- An environment where silence about racism is complicity.

- The choice of culturally relevant texts.

- Time to explore privileges and marginalization in course texts.

- Space to identify whose English “counts.”

- Lessons that teach mainstream power codes to help them become critical users of diverse language conventions (!).

ELA, the Achievement Gap and the State Budget

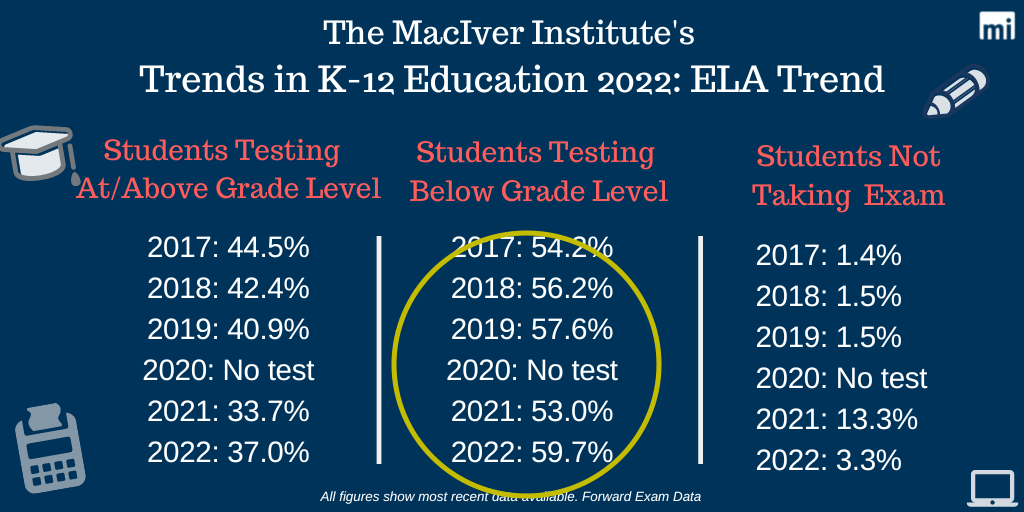

It’s no secret how poor Wisconsin’s ELA achievement scores are – we’ve covered the problems for years – the vast majority of children can’t read at grade level, and our staggering racial achievement gap makes the situation even more dire for Black students.

Governor Evers proposed $20 million for literacy in the budget, not a massive amount in the scheme of state education spending – something under $50,000 per school district. Curiously though, he proposed nearly 4 times that amount – $74 million – to boost reading instruction for bi-lingual and limited English proficient (LEP) pupils. Last school year there were about 27,000 students served as LEP students statewide. Not only is this relatively small number of students obviously not driving statewide achievement scores down, the amount of money proposed per LEP student would amount to over $2 million apiece – a confusingly high figure when across the state student reading numbers – for native English speakers – are abysmal.

McMurtry’s presentation suggested a potential reason for this strange disconnect. Perhaps the Governor and DPI intend to use those $74 LEP dollars to fund anti-racist BE, ELA2 instructional programs?

This is not out of the realm of possibility. There have been efforts for nearly 60 years to teach SE as a second language to BE-speaking students. Educators are increasingly pushing the idea that failure to give legitimacy to the native tongue of native-born Black students is part of the reason for the achievement gap – not just because they are learning another language, but that teaching SE as the “right” English devalues their culture. Increasingly, they assert that these students should be eligible for language services made available for non-native speakers.

Teaching Black English: Not a New Idea

In 1964 the linguist Raven McDavid, a professor at the University of Chicago suggested that in black communities, Standard English could be taught as a “foreign language.” In 1969 professor Charles Scott from UW Madison, used ESL pedagogy to teach writing to Black freshmen, and though his experiment is now deeply disparaged by the BE movement (he was white, thus he approached language from a colonial white supremacist position) they’ve adopted his concept if not execution.

By the 70s, National Defense of Education Act federal education dollars were used by the National Council of Teachers of English to promote students’ rights to their own language. In 1979 a federal court case in Ann Arbor, Michigan brought by parents charging black students were denied an equal educational opportunity because teachers did not recognize or accommodate Vernacular Black English. School officials were ordered to hold training sessions and develop ways to teach students who spoke it.

In 1990 the Los Angeles school district created a Language Development Program for black students, which focused on training teachers, and recognized students who spoke dialects as having “special needs.” San Francisco developed a bilingual BE pilot program in 1994 that “affirmed culture and language.”

The Oakland (CA) Unified School District unanimously declared BE as a second language all the way back in 1996, the first district to do so, saying they had failed to adequately educate black students. Some lauded the move as historic – and noted it opened up the option to apply for federal funding for ESL learners – but others urged caution citing a lack of research to show it would address achievement problems of black students.

The California state superintendent expressed concern that it could become a way to lower standards. At that time, BE was more often called Ebonics, and supporters of the move insisted it was a legitimate language, and that disparaging it stigmatized black students. There was a national controversy about the Oakland program, some states banned the teaching of Ebonics, and Oakland’s program was never implemented.

Trendsetting in Wisconsin

Through the years, particularly in certain states, efforts have persisted, and the anti-racist BE movement seems to be strengthening. The substantive changes in our ELA standards, highlighted by McMurtry, show the direction the education establishment is headed. In Wisconsin, the standards were finalized and implemented in the midst of the pandemic, flying under the radar as the main discussion about schools was whether they’d reopen, not how standards were being changed. But there was clearly a reason that some of the changes closely mirror the demands for linguistic justice. And it is no coincidence that one of the authors of our standards, approved in May 2020, was also one of the 6 authors of the Black Linguistic Justice Demands which NCTE published in July 2020.

We have been turned into trendsetters – guinea pigs if you will – for the anti-racism Black English movement to hijack our already-failing ELA instruction in the name of ‘justice.’