September 18, 2018

A MacIver Perspective By Bill Osmulski

The City of New London has been caught in a lie, and so far, their response has been to tell an even bigger lie.

But the budget, posted on the city’s website, disagrees with the finance director. Perhaps Radke and the spending plan should get their stories straight.

Earlier this month, I wrote “The city’s $20 wheel tax took effect on Jan. 1, and is expected to bring in $184,000 this year. Rather than going into a segregated account, it’s all being dumped into the general fund, according to the 2018 city budget.”

The city swears that’s not true.

The local paper, the New London Press Star, decided to look into it by asking the city’s numbers cruncher.

“According to Judy Radke, finance director for the city of New London, the wheel tax revenue appears in the 2018 budget, not under general fund revenue but in its own account under capital fund revenue,” the paper reported.

Radke went on to tell the paper, “We put it in as its own line item in the capital fund.”

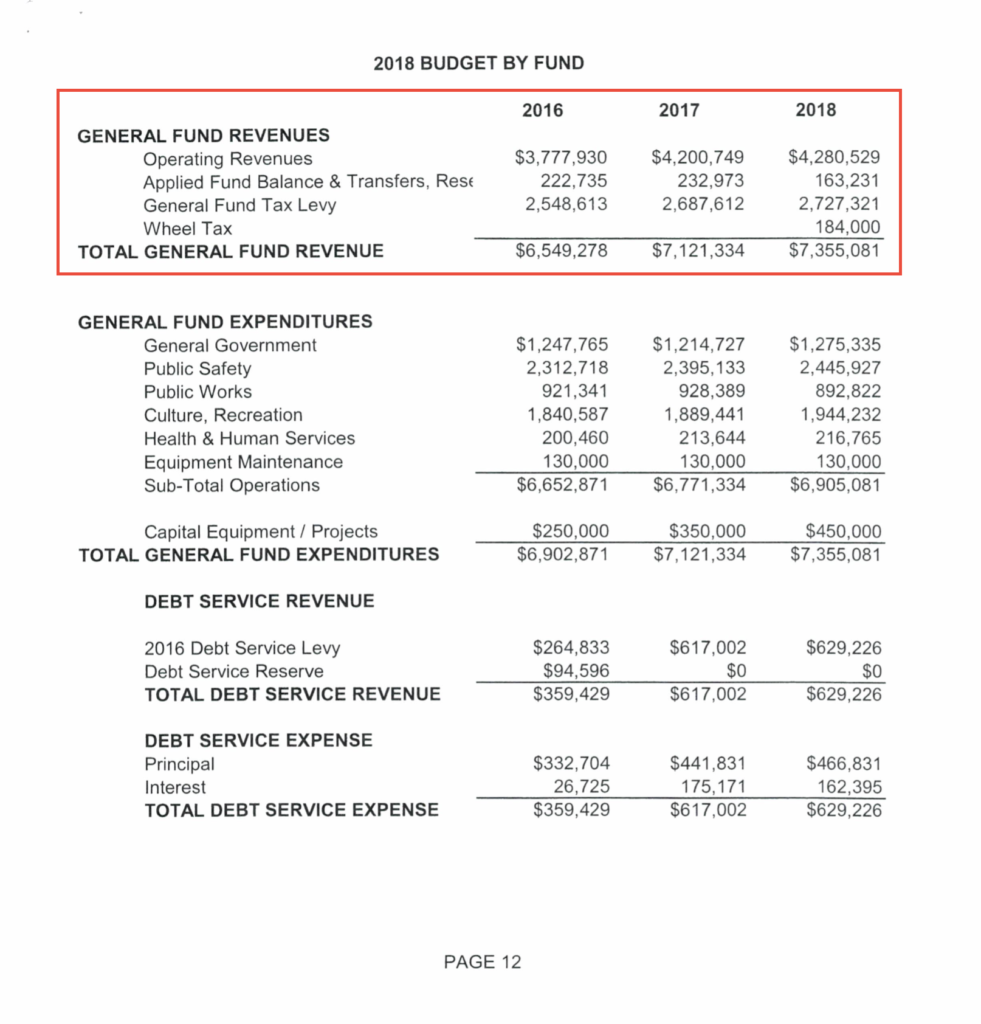

But the budget, posted on the city’s website, disagrees with the finance director. Perhaps Radke and the spending plan should get their stories straight. Here’s the link, and here’s the page that refutes Radke’s claim:

As you can plainly see, the city’s $184,000 wheel tax revenue is listed under “General Fund Revenues” resulting in a “Total General Fund Revenue” of $7,355,081. That’s not all.

The Press Star also asserts that I “did not speak to city officials for the article.” Perhaps the reporter should have checked with this reporter before writing such an inaccurate statement. Here is my email exchange with the finance director:

“Is [the capital budget] funded through bonding?” I asked on August 20th.

“They are funded through bonding, assigned fund balance and current funds,” Radke replied.

“Okay- so the city is making a $450,000 transfer from the general fund, combines it with $396,955 from the capital fund, and ends up with a total of $845,873 in capital projects and equipment spending?” I asked.

“Correct,” she replied.

“Thank you. Everything is making sense, except I can’t figure out how the wheel tax is being spent. I see it goes into the general fund at the beginning, but where does it go from there?” I asked.

“It is in the capital fund, this year it is replacing two railroad crossings and a road. Planning next year through the budget process,” She wrote.

So we have a budget document that says the wheel tax went into the general fund. We have an email exchange in which the city’s finance director does not deny it went into the general fund, nor did she attempt to correct me if I had been wrong. In her mind, the funds transferred from the general fund into the capital projects fund included the wheel tax revenue. Here, she runs into trouble again.

Last year, the city transferred $350,000 from the general fund into the capital projects fund. This year, it transferred $450,000 – a mere $100,000 increase. If the wheel tax was transferred to the capital project, the total amount transferred would be $534,000 – a $184,000 increase.

So, $84,000 was left in the general fund operating budget. How was it spent? It definitely wasn’t spent on transportation.

The Department of Public Works’ operating budget was cut by $35,000. Meanwhile, Parks and Recreation got a $54,791 boost, and spending on health care increased by $47,000 and retirement benefits increased $48,000. In fact, every city department, except public works, got an increase in funding. And so, before we even leave the operating budget, we discover that the city of New London took $84,000 of wheel tax revenue and spent it on non-transportation items.

Moving on to the capital budget, which now supposedly has an extra $100,000 from the wheel tax, we find transportation spending cut by $127,000, while the fund balance only grows by $8,000. Again, the wheel tax revenue did not go to transportation and it was not saved for future transportation projects either. When the rail crossing projects were proposed seven months later, New London couldn’t spend the wheel tax money on them, because it had already been spent.

So where did the $100,000 wheel tax revenue in the capital budget go? Parks and Recreation is once again a good place to start. Its capital spending increased by $72,000 this year.

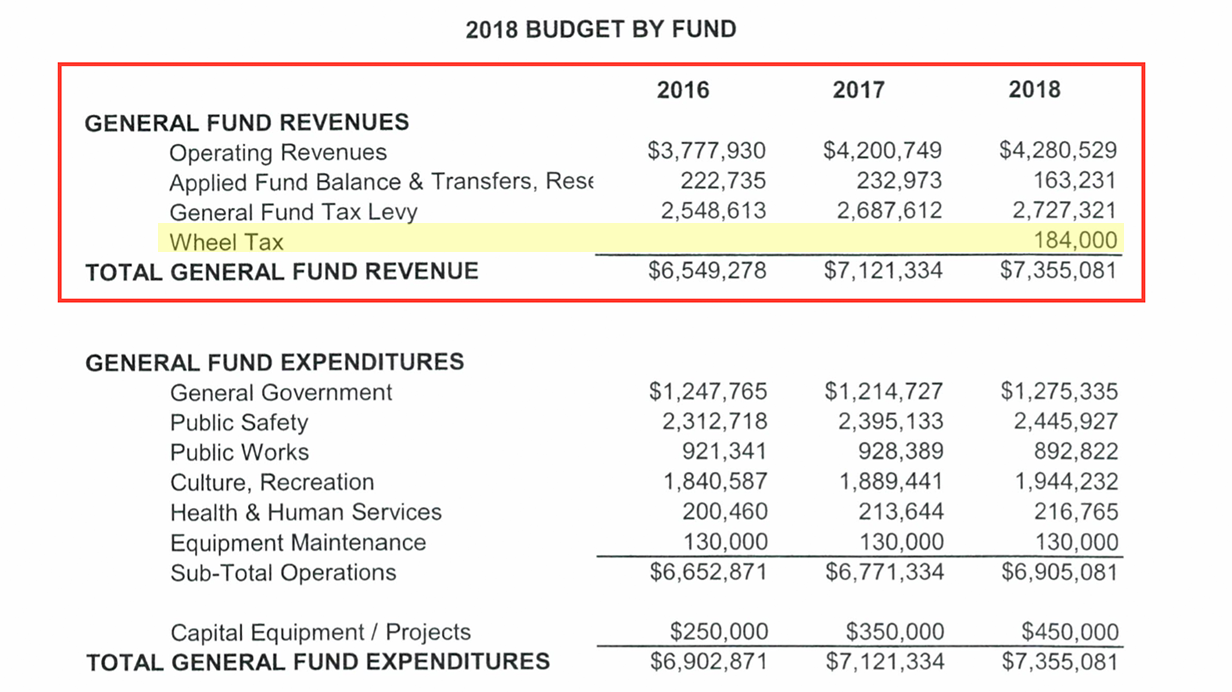

Nobody, other than me, seems interested in examining the actual budget document – which is why I’ve had to extract the relevant section and prominently include it in this response.

It’s not just the local paper circling the wagons to defend the city’s actions. The League of Wisconsin Municipalities Executive Director Jerry Deschane emailed the MacIver Institute on Monday.

“I read both of the articles on New London’s wheel tax… Your reporter’s analysis was simply wrong.”

Nobody, other than me, seems interested in examining the actual budget document – which is why I’ve had to extract the relevant section and prominently include it in this response.

When a reporter questions a public official’s claims about city finances, and there is a publicly available document that can prove it one way or the other – it is the responsibility of other journalists and a vigilant public to confirm or refute the claim based on the actual documentation. You don’t just take the public official’s word for it, who has been accused of being dishonest in the first place. That’s beyond lazy. It’s reckless.