Last week we reported on mismanagement at the Wisconsin Department of Veterans Affairs(DVA) throughout the Evers Administration. As we review more documents, we are learning more about the depth and breadth of the crisis in the department.

Here are 5 more take-aways from public records we reviewed:

- Late last year, DVA estimated that if nothing changes in the administration of the Wisconsin Veterans Homes – e.g. the censuses stay low, the labor shortages continue, the expenditures continue – the homes will be insolvent by fiscal year 2027 in spite of millions of pandemic aid dollars flowing in to DVA.

- The census at King and Union Grove are about half their capacity and well below the level required to sustain operations. Yet even with contract staff, forced overtime is still required of staff.

- Purchasing rules have been waived for the department, allowing them to avoid a bidding process, and continue paying price-gouging rates for staffing contracts.

- A toxic workplace is cited by staff and family alike as a factor in much of the turnover and continued staffing problems.

- Secretary Kolar has ignored repeated concerns voiced from leadership in the homes about the management of her appointee, Veterans Homes Administrator Diane Lynch, contributing to high staff turnover.

And 1 takeaway about DVAs handling of open records requests:

- The department applies different standards of redaction to the same responsive documents, apparently based on who has made the public records request.

Over-Reliance on and Overpaying for Contract Staff

In the records we viewed, the department consistently responds to press inquiries by saying they use temp agency staff as a “short term” resource to maintain adequate staff levels.

This is not an accurate characterization of DVAs use of temp agency staff.

It is not unusual for public and private health care facilities to occasionally use contract staff to fill in staffing gaps on what are generally short-term basis. In private facilities, the use of temporary agency staff must be minimized because it’s not cost-effective long-term.

In state agencies, it may be used slightly more often than in the private sector because government agencies have much less flexibility working within the civil service system. The lag time between application and hiring in government can be unmanageable when trying to address sudden, critical needs.

However, none of that would explain the constant use of temporary agency contract staff at Union Grove, or why a plan was never developed to stabilize facility staffing and by doing so, put an end to the excessive expenditures.

It appears that during the Evers Administration, the only staffing plan at the Veterans Homes was constant contracting and contract extensions for high-cost temp staff. Lynch herself described her staffing efforts as being in “endless procurement jail.” How much they’ve spent on contract staffing is hard to tell based on the records we have reviewed – and it’s not even clear that DVA leadership is effectively tracking their expenditures.

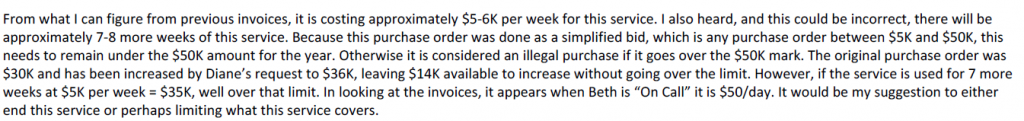

A lengthy email exchange earlier this year between multiple DVA staff including a purchasing manager and the homes administrator shows confusion over invoicing intervals, the cost of the contracts per week, and when the purchase order limit would be reached for contract staff.

DVA is currently recruiting for Certified Nursing Assistants (CNAs) at an hourly rate of $18.82, plus a $5 per hour temporary add on through June 17, 2023 (just before the end of the fiscal year), and a $2,000 sign-on bonus. The bonus is paid half in the first paycheck and half when the employee reaches permanent status.

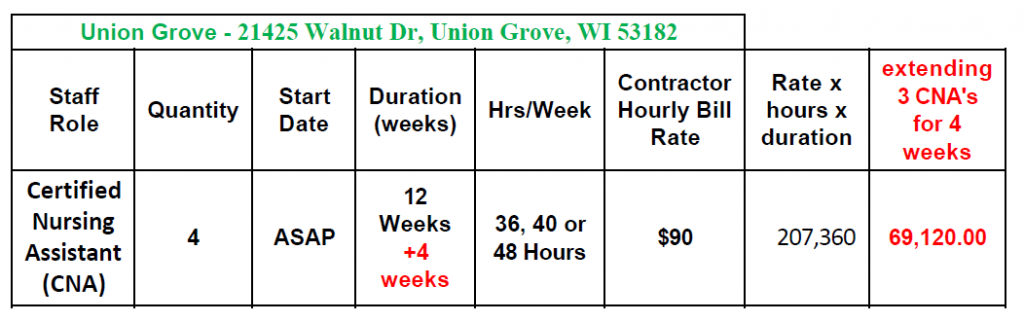

As recently as this summer, records show the Department was still paying a staffing agency $90 per hour for CNAs at Union Grove.

End-Running Procurement Rules

On at least one occasion, DVA got the Department of Administration’s (DOA) procurement section to end-run the normal bid threshold, which prevents agencies from contracting for services over $50,000 without going to competitive bid, by giving DVA a special “waiver.” DOA approved this mile-wide loophole based on the argument that staffing is required by law.

It’s unclear from these records exactly how many agencies DVA contracted with, or that the Departments of Health Services (DHS) or Corrections contracted with where DVA piggy-backed onto the existing contracts, but there appear to have been more than a dozen.

What is clear is that the DVA used many contractors, perhaps in another strategy to avoid going to bid, and that the cost was no object. It looks like the cost was never even a consideration. The most expensive vendor we saw in these records was NuWest, which DVA used, and extended contracts with for multiple staff at price-gouging rates.

Management Failures

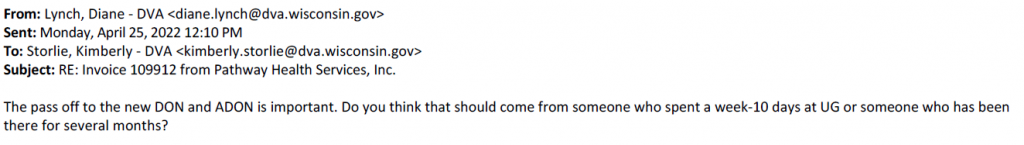

With approval and support of the secretary’s office, Diane Lynch, the Veterans Homes Administrator appointed by Kolar, requested extension after extension of temp staff contracts, ran up against procurement limit rules, and was seemingly unable to assess or address staffing needs and stabilize spending.

Meanwhile, department employees who volunteered for overtime had their shifts taken away and given to the more expensive contract staff, while others were moved around between shifts so that they never had a consistent window during which to sleep. Others who worked 60+ hour weeks were penalized for being 5-10 minutes late for work; others, in spite of picking up many overtime hours, were scheduled on the one day they could not work.

Staff and families at Union Grove have written Kolar and Lynch for years now, begging for a solution to the excessive use of forced overtime that landed at least one aide in an ambulance, another in a ditch and caused many resignations.

But while overseeing staffing levels that resulted in forced 16 hour back-to-back shifts for staff who do a great deal of physical work, Lynch emailed Kolar in June of 2021 saying she was being asked to do more than her normal job, that her days spent at Union Grove might last 12 hours (including commute) and that she was fatigued and stressed. Lynch asked – and was granted – permission to dial back her work hours on-site in the struggling home which was desperately in need of management and leadership.

The following month, Lynch sent staff, already being forced to work back-to-back overtime shifts, a memo stating, “The only time you should be sitting is when all your work is done.”

In May 2022, the nursing staff said the facility was down to 13 FTE nurses when 24 were needed.

And May 2022 is also when, in approving yet another contract extension for $90/hour CNAs, Deputy Secretary Bond thought to ask Lynch for a staffing plan to deal with shortages. It’s unclear whether he had finally thought of it, or whether it came out of a measure of irritation that the money for the staffing extension would reduce the pandemic funds available for the building demolition plan he favored.

DVA’s Toxic Culture

The workplace culture of DVA has been described in these records as “toxic” by both staff and family of members. The emails reveal agency leaders focused more on finger-pointing than problem-solving.

The Assistant Deputy Secretary tattles on the budget office staff.

Human resources is hurt because they feel unfairly blamed for staff troubles.

Lynch regularly complains about home staff she thinks are unable to manage the basics of their job. Her tone in responding to questions from the current commandant asking for advice on a potential way to save money while assuring coverage can only be described as snippy and demeaning – something a previous commandant noted as problematic.

Any outside criticism or questions – such as Congressman Steil’s concern with the U.S. DVA’s revelation that the state DVA rejected their offer of help – are not taken to heart, even internally, and simply branded lies.

A rare, pointed question from a reporter referencing some loss of staff due to forced overtime – something indisputably happening – was termed “overly simplistic” in internal discussions on how to respond.

And as recently as this spring, the secretary’s office believed Union Grove had enough regular employees to adequately care for the members, and that the costly contract staff are unnecessary. This while staff were being forced to work overtime and the home was receiving citations for deficiencies in care.

Agency leadership doesn’t acknowledge or doesn’t understand the staffing problems, yet their management strategy is to continue to extend high-dollar contracts for additional staff they believe are necessary.

In short, the organization is long on drama and short on solutions.

An organization in crisis needs leaders who are able to cut through this kind of pettiness, focus on solving their problems, and steer toward stability.

Instead, there has been a revolving door of staff in the homes, due to a toxic combination of mismanagement and, at least on the part of some of the commandants, concerns about vindictiveness from Lynch. Union Grove has had 5 commandants in under 4 years.

Kolar and Bond received emails from at least two of the 4 former commandants, one asking for a meeting without Lynch to discuss concerns about staff being vindictively pushed out, and another voicing specific concerns that staff morale was impacted by Lynch being demeaning, bullying, and subtly threatening.

Both commandants were soon gone.

When yet another of Union Grove’s commandants left after just months on the job, Kolar and Bond received an email from the executive director of Ainsworth Hall at the King home, a licensed nursing home administrator with a long career in private sector nursing home administration in multiple states. Douglas Wamack had been reassigned to Union Grove in June by Lynch after the facility racked up 12 deficiencies in the May 2021 survey.

In his email to the secretary, Wamack says Lynch was “directly responsible” for the bad survey at Union Grove he was being asked to “clean up,” by having made bad hiring decisions and “cutting staff to the quick.”

He resigned from state service just a week after being moved to Union Grove.

Incidentally, this was in June of 2021, the same month Lynch asked to spend less time in the homes due to her stress and overwork.

Union Grove Veterans Home has had 47 deficiencies, an average of 1 every month of the Evers Administration, a record that puts it among the most deficient veterans homes in the nation. Staff turnover is high, there are obvious management problems, and millions have been spent on temporary staffing only to see the census fall to half the level it was before Evers took office. The agency has been allowed to skirt procurement rules while they contract for temporary staff rather than develop a plan to retain staff.

It is an agency in crisis.

Next biennium, whoever is in the Governor’s seat needs to do an overhaul of agency leadership who have driven these homes to the brink of insolvency and bring in talented and knowledgeable problem-solving managers to lead the agency.

The department should also be scrutinized for their handling of open records requests. Standards for what information is redacted from tresponsive documents should not vary based on the requesting individual or other criteria, as is current practice based on differences in cover letters laying out redactions and the redactions made (or not made) in the same responsive documents. This is of deep concern, particularly if it is widespread practice across the Evers Administration.

The records we’ve reviewed from multiple open records requests of the agency give a window into the mismanagement of DVA, but in no way do they paint a full picture. In truth, the records raise more questions than they answer.

Here are a few:

- Why is there no staffing plan for the homes?

- What is the plan for avoiding the homes becoming insolvent?

- How many pandemic aid dollars are going to tear down old buildings owned by DVA?

- Why don’t the vacancy reports provided to the legislature include the contract staff, and the division between employees and contract staff?

- How much has been spent, and from what allocations of funds, on temp staffing by year since 2018? This should include piggybacking on other agency staffing contracts, or any payments made to other agencies for staffing they paid for under their contracts, as well as the cost of the National Guard staff and the U.S. DVA staff.

- Why does Open Book seem not to contain full information on the homes’ staffing expenditures?

- How many times has DOA allowed agencies to bypass procurement rules smoothing the way for agencies to contract for services that should have gone to bid?

- How many staff that worked at Union Grove in 2018 still work there?

- How many individual staff not employed directly by DVA including contract, U.S. DVA and National Guard have rotated through Union Grove since 2018?

- How many temp staff are currently working at Union Grove? At what rate(s)?

- King and Union Grove are operating at around half capacity; is there a plan to bring the census up to or near previous levels?