Dec. 2, 2020

Right from the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis, contact tracing has been a key component to the Evers Administration’s strategy to slow the spread of the virus in Wisconsin.

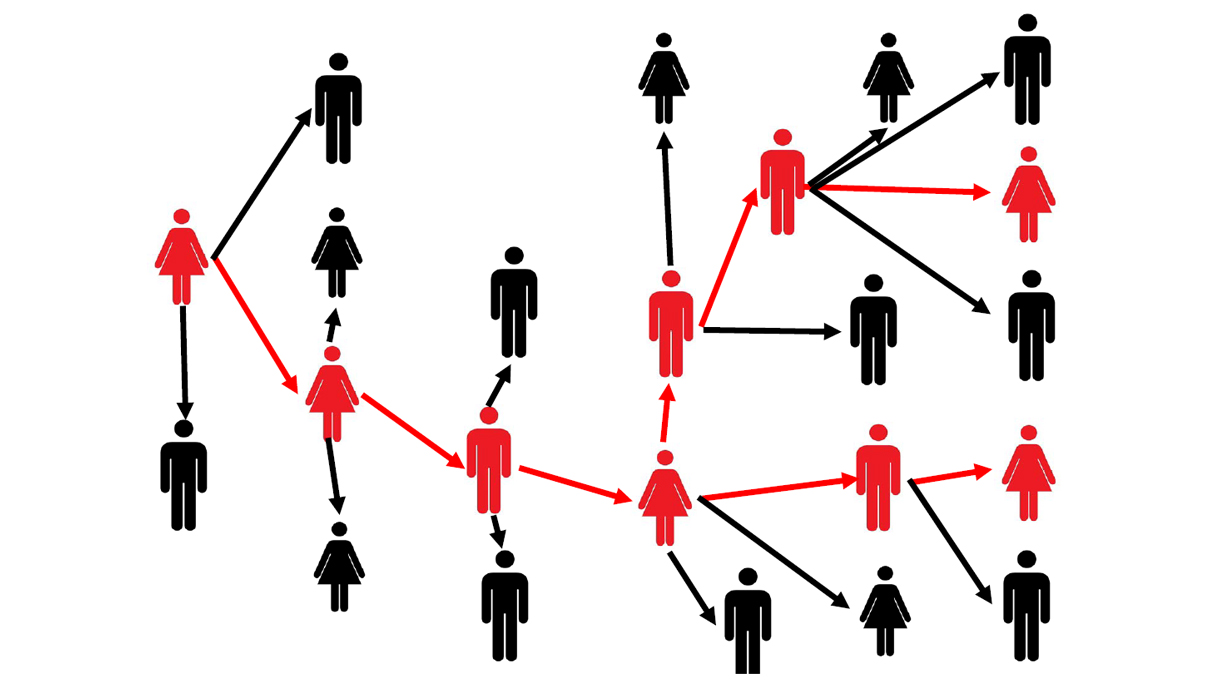

Contact tracing takes place after an individual tests positive for COVID-19. A government worker attempts to map out that person’s recent social interactions, and then contact all those people to warn them they’ve potentially been exposed to the virus.

“Contact tracing is a critical tool in our ability to effectively manage COVID-19 now and moving forward,” said DHS Secretary-designee Andrea Palm on April 9th.

The theory behind contact tracing seems sound. If you could quickly intervene in every individuals’ social circle whenever a new case of the virus emerged, it should be easy to snuff it out. If contact tracing was going to have this result, it probably would have happened early on.

In March and April, Governor Evers’ unconstitutional “Safer-at-Home” order was in effect, which significantly limited everyone’s social interactions. No one was supposed to interact with more than five people, and preferably those people would all live in the same household.

In April, Wisconsin was averaging 184 new COVID cases every day. At that time, there were about 400 contact tracers throughout the state. Even with that 2-to-1 advantage, DHS said contact tracers couldn’t keep up.

If 400 tracers couldn’t handle 184 cases a day in April, what chance do 1,200 tracers have against 5,400?

“Just think about what we’re aiming to do. If we conduct 85,000 tests per week, and 10% are positive, as we’re seeing now, we will need to interview 8,500 people. And if each of them has five contacts, that’s another 42,500 people to call. We’re not there yet, but we’re making progress,” DHS Deputy Secretary Julie Willems Van Dijk said during an April press conference.

After the state supreme court ruled “Safer-at-Home” was unconstitutional, Gov. Evers’ options were limited. He decided to double down on contact tracing.

“Contact tracing is critical to our boxing in the virus, and your willingness to pick up the phone and help with this piece of our state’s response to COVID-19 is essential to our success,” Palm said on May 21st.

Gov. Evers used $75 million from the federal CARES Act to fund a massive hiring initiative. (Only $15 million was allotted for a single, poorly-placed overflow facility.) By the end of October, there were over 1,200 people working as contact tracers throughout Wisconsin. Most of them were hired by local governments, with 373 working directly for the state.

Meanwhile, the average number of new cases rose to 5,400 during November. If 400 tracers couldn’t handle 184 cases a day in April, what chance do 1,200 tracers have against 5,400?

Dr. Ryan Westergaard, Wisconsin’s Chief Medical Officer, said Wisconsin needed far more contact tracers to be successful.

“With the current level of staffing and financial resources, state, local, and tribal health departments may not be able to feasibly achieve goals that have been set for completing disease investigations and contact tracing interviews at all times,” he said.

Westergaard recommended contact tracers prioritize types of social contacts to focus on. The highest priorities on the DHS list are people you live with, significant others and best friends – people who would know right away if their loved one tested positive without government help. The lowest priority on his list are large gatherings, events, and places like bars and grocery stores – where people would be least likely to know they came into contact with someone who tested positive.

Needless to say, contact tracers report people are becoming suspicious. They’ve noticed people have become increasingly more guarded with what personal information they share.

“We have to get to a place where the daily number of new cases is not overwhelming the system,” Palm said for contact tracing to work.

Even though the number of cases continued to rise dramatically while the state increased its contact tracing capacity, DHS claims the effort paid off.

“Does [contact tracing] make any difference? My strong view is that the answer is yes, contact tracing can save lives, even if it isn’t successful at our overall goal, which is flattening the curve and eliminating transmission,” Dr. Ryan Westergaard said on Nov. 4.

Gov. Evers wants congress to approve more federal funding for 2021, or else the state will be on the hook for funding the contact tracers itself.

How many contact tracers will it take to handle this problem? No one’s giving specifics, but we already know that having twice as many tracers as new cases is not enough. That means even if the state paid for another 9,000 tracers, it would still not be enough. Will it ever be enough?

(DHS has announced plans to release a smart phone app to automate contact tracing. The app will keep track of other cell phones in its proximity. If the owner of one of those phones tests positive, the app will notify anyone who was in contact with them and, of course, has the app on their phone. Given how suspicious people are of providing personal information to contact tracers over the phone, it seems unlikely many people will download a government GPS tracking app directly onto their phones.)