MacIver News Service | May 14, 2019

By M.D. Kittle

MADISON, Wis. — It may be legal, but a federal funding transfer program that siphons more Medicaid money for University of Wisconsin Health and the state of Wisconsin looks a lot like a scam on taxpayers.

A former health care executive instrumental in creating the state’s largest public health endowment says the Certified Public Expenditure (CPE) program, specially carved out for the health care provider, raises some serious questions.

The Certified Public Expenditure program allows DHS to receive additional federal funds based on the difference between the federal reimbursement rate for the services provided by UW Health and the actual cost of providing them.

“Everybody takes a cut,” said Thomas Hefty, former chairman and CEO of the old Blue Cross and Blue Shield United of Wisconsin. “Should taxpayers be paying this?” Hefty and Blue Cross and Blue Shield helped set up the $300 million-plus endowment fund at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

The CPE “mechanism” designed to draw more Medicaid cash into the coffers of the state and UW Health, the integrated health system of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, is a carve-out for the UW health care provider that others don’t receive. The former director of the state Department of Health Services, Karen Timberlake, was at the helm when the “innovative financing” scheme was established. Soon after, she landed a gig with the University of Wisconsin-Madison and a sizable grant.

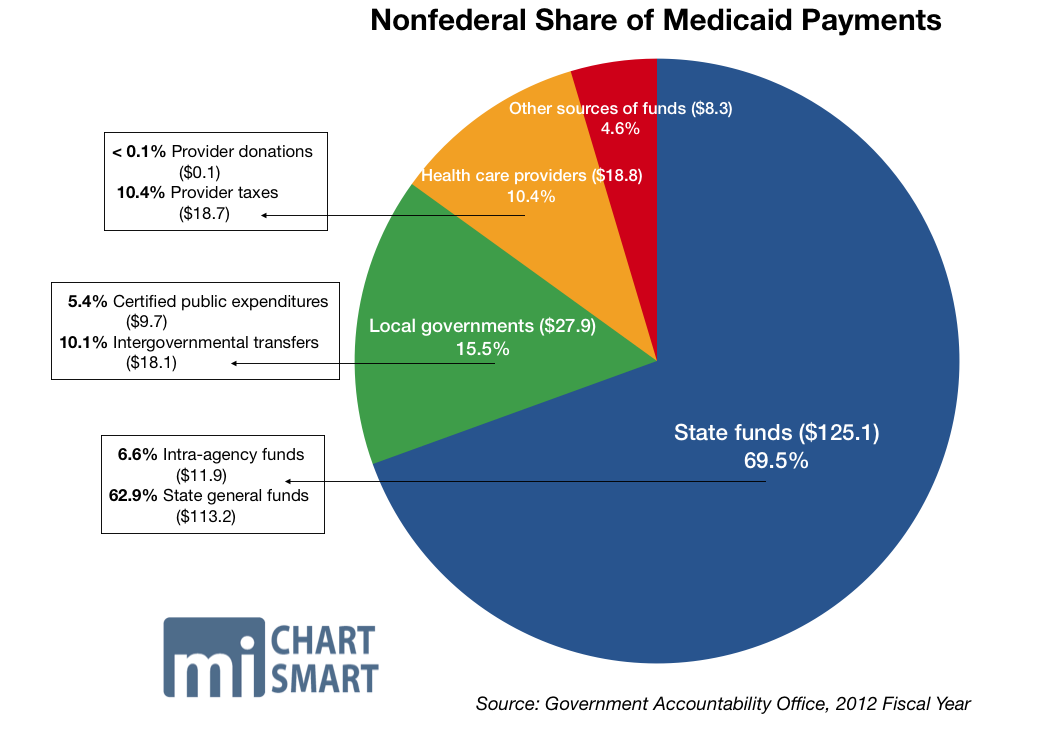

More so, the special agreement begs a broader question. Why are there so many funding schemes to attract more federal Medicaid funding into states? Taxpayers can be forgiven for struggling to understand the complex formulas involved in Medicaid funding, and Wisconsin health care providers can be forgiven for their frustration over low reimbursement rates. A national system designed to take care of the health care needs of the poor is not delivering nearly enough funding to meet the rising costs of health care in many states.

Why not just set reasonable reimbursement rates rather than fabricating sleight-of-hand schemes for state government players? And is the taxpayer getting burned by the rules of a complicated numbers game? Federal accounting experts say, in some cases, yes.

Creative financing

Red flags arose for Hefty while reading through an outside audit of the University of Wisconsin System, the first of its kind. The audit highlighted the Certified Public Expenditure agreement between UW Health, the state of Wisconsin and the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

During the 2007-08 fiscal year, the Wisconsin Department of Health Services implemented the CPE program for the services that the University of Wisconsin faculty physicians group provides to Medical Assistance recipients. The idea was to draw “matching funds” or additional funding claimed under Medical Assistance.

As noted in the December 2018 independent audit of the University of Wisconsin System, the Certified Public Expenditure program allows DHS to receive additional federal Medical Assistance funds based on “the difference between the (government) established MA reimbursement rate for the services provided by the UW-Madison faculty physicians group and the actual cost of providing those services.”

Bureaucrats assert the IGT agreements help Wisconsin health care providers make up for some of the lowest Medical Assistance reimbursements in the nation.

The federal Medicaid reimbursement rate for Wisconsin is 59.36 percent, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. Wisconsin had the 4th-lowest Medicaid-related primary care repayment rates, at 71 percent of cost, according to Kaiser State Health Facts.

UW was able to up those numbers, thanks to the special CPE program.

To enable the “draw” of the additional federal funds by the state Department of Health Services, UW-Madison sent to DHS a total of $11.3 million in fiscal year 2018, “representing the state’s share of the difference.”

The federal Medicaid reimbursement rate for Wisconsin is 59.36 percent. Wisconsin had the 4th-lowest Medicaid-related primary care repayment rates, at 71 percent of cost.

“DHS then claimed the federal share of the difference from the federal government and subsequently provided $26.6 million … representing both the state and federal share of the difference, to the University of Wisconsin Medical Foundation,” the audit notes.

There are a lot of players involved. Ultimately, the University of Wisconsin Hospital & Clinics Authority is the governing entity of UW Health, UW Hospital, and the UW Medical Foundation.

The same occurred in 2017, with DHS providing $26.1 million to the foundation after UW-Madison remitted $8.5 million to the state agency. The transfers represented a gain of more than $15 million in the last fiscal year, and $17.6 million in 2017.

“In addition, UW-Madison incurred expenditures for which reimbursement was received from the UWMF. Of the $114.5 million expended in fiscal year 2018, $101.8 million was for salaries and fringe benefits of staff in the UW-Madison School of Medicine. In fiscal year 2017, of the $103.7 million expended, $91.9 million was for salaries and fringe benefits of staff in the UW-Madison School of Medicine,” the audit notes.

“There are multiple issues here. Is it legal? Is it the right thing to do? What is the level of skimming going on?” Hefty said.

And, why does UW Health get what amounts to a special deal, drawing in another source of funding that other hospitals don’t receive?

’Specific conditions’

The Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services pointed to federal regulations that allow for public funds to be considered as the state’s share in claiming Federal Financial Participation (FFP) funds “if the funds meet specific conditions.” A CMS official said Wisconsin has an approved Medicaid state plan. CMS did not answer how the state has given assurance that it will “abide by Federal rules and may claim Federal matching funds for its program activities.”

States are required to obtain approval for the use of such funding, according to CMS.

“CMS requires the states to describe how the state share of Medicaid payment is funded, whether it be from an appropriation from the Legislature, an IGT (intergovernmental transfer), a CPE or other mechanism,” the agency noted in an email to MacIver News Service.

CMS did not provide a specific approval document, it only pointed to volumes of various state plan amendments over the years. None appeared to answer MacIver News Service’s questions.

The Department of Health Services did not answer MacIver News Service’s questions about the Certified Public Expenditure program, despite repeated requests beginning late last month.

State’s take

UW Health spokeswoman Lisa Brunette said the health care provider follows all rules, regulations and laws governing business operations.

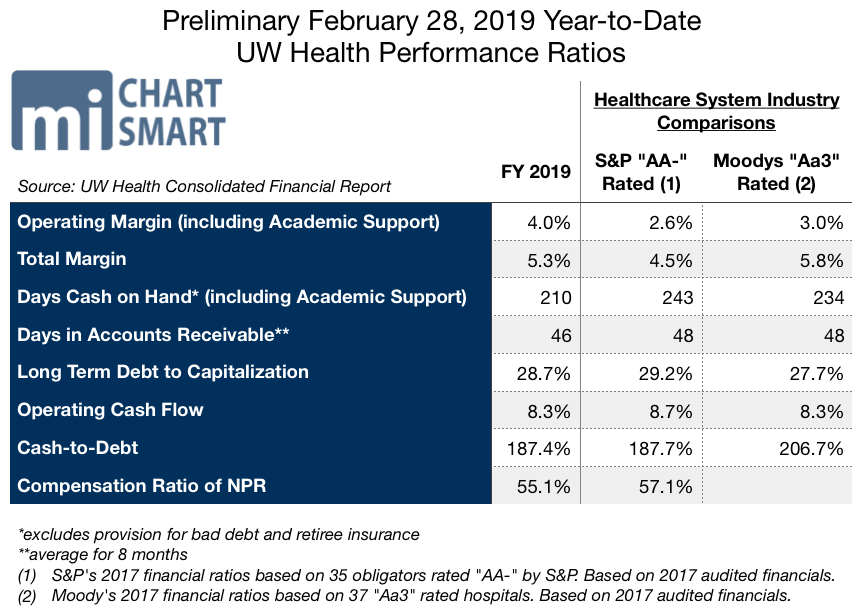

February minutes of the UW Hospital and Clinics Authority Board show the health care provider’s profitability as a percent of revenue is nearly 30 percent higher than peer AA rated health care groups.

“When a Wisconsin Medicaid patient is treated at UW Hospitals, Medicaid is billed for the care provided. The state Medicaid program pays the hospital for that service, but the amount paid does not cover the costs of treatment. The hospital certifies the resulting losses as certified public expenditures and reports those losses to the state of Wisconsin through the CPE process but the hospital does not receive those funds back. They stay with the state of Wisconsin,” Brunette said in an email.

She said the UW Medical Foundation “does not retain any of the funds it receives through the IGT process.” But UW Health gets a share.

Why should taxpayers across the country have to cover the costs of this federal revenue enhancement system?

“This program is intended to benefit all MA providers in the state and by extension, the patients they take care of. UW Health, unlike many other public hospitals, does not keep all or most of the funds. The money is used to fund a program that still doesn’t even cover the cost of the care provided,” Brunette said.

Hefty took issue with UW Health’s pleading of poverty. February minutes of the UW Hospital and Clinics Authority Board show the health care provider’s profitability as a percent of revenue is nearly 30 percent higher than peer AA rated health care groups.

There are some interesting connections in the “flexible” world of Medicaid payments. Former Gov. Jim Doyle’s Department of Health Services secretary, Karen Timberlake, was subsequently hired as an associate professor at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health and served as director of the UW Population Health Institute. She received $500,000 for her project, paid for by the Blue Cross endowment fund.

Timberlake now serves as a senior member of powerhouse law firm Michael Best. She recently served as a member of Democratic Gov. Tony Evers’ Health Policy Advisory Council.

Other schemes

The “innovative financing mechanisms” go back to 2001, when then-Gov. Scott McCallum, a Republican, and the Legislature came to terms on a Medicaid intergovernmental transfer program. The deal, spurred by the nursing home industry, allows counties to borrow money from financial institutions and transfer the cash to the state, which then returns the funds to the counties and certifies the returned money as Medicaid expenditures for nursing facilities. That enables the state to claim federal matching funds, worth about $600 million in additional federal funding for Wisconsin’s coffers during the 2001-03 budget, the first budget in which the transfer was in effect.

The funds are to be used to increase payments to nursing facilities, “particularly facilities that are run by the counties,” according to a March 2002 report from the Urban Institute.

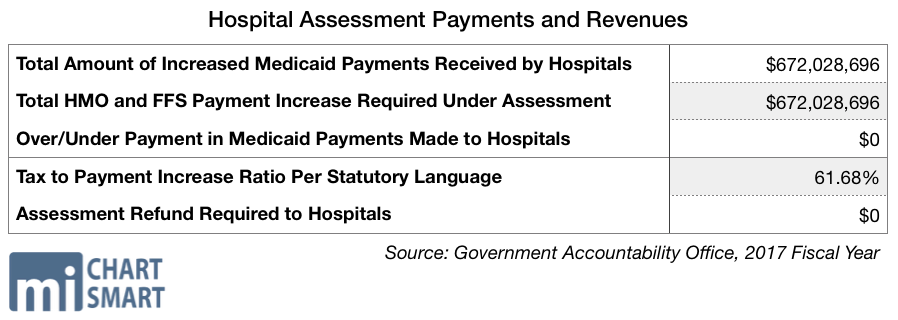

The hospital tax, which draws in additional federal funding, is redistributed back to the hospitals to help cover the costs of Medicaid-related services.

A few years later, then-Gov. Jim Doyle, a Democrat, and the Democratic-controlled Legislature pushed through a tax — or assessment — on Wisconsin hospitals. Under the program, the state Department of Health Services collects quarterly payments on the health care centers. The tax, which draws in additional federal funding, is redistributed back to the hospitals to help cover the costs of Medicaid-related services.

“The purpose of the assessment is to return a portion of the assessment, combined with associated federal matching funds, to hospitals through MA supplemental payments, while also using the remaining SEG revenue to supplement GPR funding for the MA program as a whole,” notes a report on Medicaid from the nonpartisan Legislative Fiscal Bureau.

In pitching the plan in 2009, Doyle said every $1 of tax revenue raised from the hospitals would attract about $1.65 for the health care providers from the federal government.

Ultimately, the Wisconsin Hospitals Association was onboard, as were other business advocates.

In 2017, the total combined amount of increased Medicaid payments received by the hospitals topped $672 million. The University of Wisconsin Hospital & Clinics Authority is part of the assessment system, according to the Department of Health Services. In 2017, it paid in $34.77 million. It received a total of $78.46 million in Fee For Service payments, with a total increase in its FFS of $17.84 million.

In 2018, total Medicaid spending in Wisconsin (state and federal combined) topped $8.2 billion.

High risk

“The IGT program is controversial, but even critics of the IGT approach admit that the state does not have any other politically viable options to generate the same level of funding for nursing facilities that the IGT affords,” the 2002 Urban Institute report concluded.

Such transfers are indeed controversial, and they have for years fattened the revenue cash cows of state governments, as well as participating players — at federal taxpayer expense.

The U.S. Government Accountability Office designated the $629 billion Medicaid program ($393 billion paid for by the federal government) as high risk in 2003 because of concerns about federal oversight of this “large, growing, and complex program.” GAO’s review, noting that the system “gives states an incentive to overreport their Medicaid expenditures … identified “state schemes” that shift money between state accounts to “create the illusion” of higher Medicaid expenditures.

The Government Accountability Office estimated improper payments — including payments made for people not eligible for Medicaid or for services not actually provided —was 9.8 percent of Medicaid spending, or $36.2 billion in fiscal year 2018.

“Similarly, some states have spent their federal Medicaid dollars on non-Medicaid purposes,” the GAO report stated. “Tight state budgets like those experienced by most states today have increased the pressure for such deceptive tactics.”

MacIver News Service found no evidence that the federal money raked in by the state of Wisconsin was used for inappropriate purposes, but federal inspections have found previous problems. DHS “did not report all Medicaid overpayments in accordance with Federal requirements” in fiscal year 2006 and 2007, according to the Office of Inspector General for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

“(W)e estimated that the State agency did not report Medicaid overpayments totaling $720,563 ($427,445 Federal share) in accordance with Federal requirements,” stated the OIG report, issued to Timberlake in May 2010. Twenty of the 131 overpayments that the inspector general reviewed were partially or not reported properly. The state Health department did not report all Medicaid provider overpayments within the 60-day time requirement, the review found.

More than a dozen years later, the “creative” funding mechanisms employed raise questions about the transfer system in general.

State budgets are heavily bolstered by schemes to draw more federal funding. Doyle made it an objective in his budgets.

“Continue to pursue innovative financing mechanisms to increase federal intergovernmental transfer revenue to the state by $547 million,” the Democrat noted in his 2003-05 budget proposal summary. It was included under the subhead, “Restoring Fiscal Discipline.” Governors across the country have set similar goals over the past couple of decades.

A 2016 Government Accountability Office examination of Medicaid supplemental payments in Florida, Texas, Oklahoma and New Mexico tracks some of the problems. The report, spurred by a previous GAO investigation that found 505 hospitals nationally drew in $2.7 billion in Medicaid payment surpluses, found not all hospitals in the review “tracked their use of revenues from the large supplemental payments they received and tracking of revenues is generally not required.”

“Based on information obtained from hospital officials and a review of demonstration approval documents, GAO determined that the revenues were used for a broad range of purposes,” the review found. Nine hospitals used the surplus revenue to fund general hospital operations, establish poison control centers, and make capital purchases, such as a helicopter.

“Three selected states distributed Medicaid supplemental payments largely based on the availability of local government funds to finance the nonfederal share of the payments, rather than on the services the hospitals provided. Medicaid payments should be made for Medicaid services or, if under demonstrations, for demonstration purposes and [to] be economical and efficient. GAO found that three states made supplemental payments based on the ability of hospitals, or their local governments, to finance the nonfederal share. Consequently, hospitals otherwise eligible for payments but whose local government could not finance them did not receive them,” the report notes.

Fraud and oversight in general continue to be a problem in the Medicaid program.

More recently, the Government Accountability Office estimated improper payments — including payments made for people not eligible for Medicaid or for services not actually provided —was 9.8 percent of Medicaid spending, or $36.2 billion in fiscal year 2018.

“CMS needs to improve the effectiveness of its oversight of improper payments and related payment risks…” a recent GAO report notes.