May 13, 2019

By Bill Osmulski

The narrative has been set for years: local roads in Wisconsin are falling apart and local governments need more road aid from the state to fix them. What’s left out of that narrative is how much state taxpayers are already giving to local governments in road aid, and how little of that road aid is actually going towards fixing roads. Wisconsin’s townships are the worst offenders.

How the Department of Revenue Tracks Transportation Spending

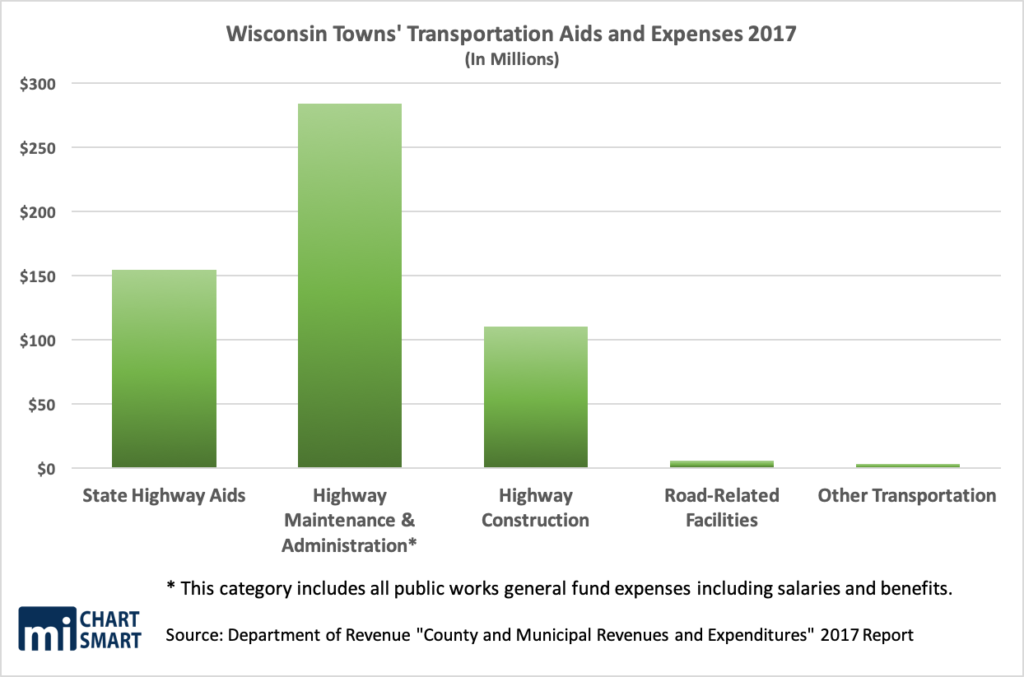

Most towns do not post their budgets online, but fortunately, the Department of Revenue collects, collates, and publishes every local government’s financial information online. The most recent data is from the year 2017. Transportation expenses are recorded in four separate categories: “highway construction,” “highway maintenance and administration,” “road related facilities,” and “other transportation.”

When people talk about fixing roads, they are talking about the “highway construction” category. That includes resurfacing and reconstruction road work. Note, when local governments take on highway construction projects, they don’t always use state aid to pay for it. Because these are capital projects, it’s common for local governments to fund them through a debt levy (which isn’t subject to tax levy caps), and push the state aid to the next category: “highway maintenance and administration.”

Now “highway maintenance and administration” sounds like it would play a big role in fixing roads, but the label is deceptive. Yes, some of it does go to filling potholes and sealing cracks, but it also includes all general fund expenditures in a local government’s public works department. That means salaries, benefits, and utilities in addition to road repair materials. Nobody expects state road aid to go to the local public works director’s salary and retirement, but it does. By examining individual local governments’ budgets with an itemized breakdown, it’s often revealed that repair materials make up a very small portion of these expenses.

Nobody expects state road aid to go to the local public works director’s salary and retirement, but it does.

“Road related facilities” are buildings that are typically funded as capital projects with bonding. Local governments almost always pay those bonds back by collecting a debt levy, in additional to the tax levy. Again, debt levies are not subject to levy caps, which is why property taxes usually shoot up whenever a local government renovates or constructs new buildings.

“Other transportation” means mass transit. In other words, not roads.

For many local governments, these expenses are important because they are used in a cost-sharing formula to calculate how much road aid they get from the state. However, that’s not the only way the state disburses those funds.

How the Department of Transportation Calculates Road Aids

Local governments receive state transportation aid primarily through three programs: the Local Road Improvement Program (LRIP), the Local Bridge Improvement Assistance Program, and General Transportation Aids (GTA). There is some cost sharing involved in the first two programs, but it is not required to receive GTA, which provides the vast majority of road aid to local governments. Over the past two years, towns have received $10 million through LRIP, shared $86 million with cities and villages through the bridge program, and received $300 million from GTA.

97 percent of Wisconsin’s towns spent so little on road work, they are better off taking the flat rate instead of using the cost sharing formula.

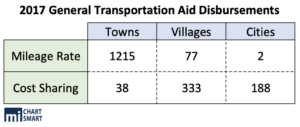

There are two methods to calculate how much GTA the state gives a local government. Some receive funds based on a cost-sharing formula (which considers everything even remotely associated with roads, like traffic enforcement), and the other is a flat-rate based on how many miles of road the local government is responsible for. Communities with large police and public works departments typically go for the cost-sharing formula. Communities that spend very little on transportation go for the mileage rate. Almost all Wisconsin’s towns use the mileage rate.

According to the DOR in 2017, out of 1,253 towns, 1,215 of them took the mileage-based aid. In other words, 97 percent of Wisconsin’s towns spent so little on road work, they are better off taking the flat rate instead of using the cost sharing formula.

Mike Koles, Wisconsin Towns Association Executive Director, recently claimed that the MacIver Institute “ignores the local contribution required to receive GTA, LRIP, and bridge aids. Simply, due to the cost share formulas of these programs, it’s not possible to have towns getting state aid and spending zero on roads as they falsely purport.”

However, during a transportation funding task force meeting on Jan. 30, Koles stated that towns do not typically receive aid through the cost sharing formula, which he criticized for its inclusion of non-road items like traffic enforcement.

“Part of the challenge is what goes into the shared cost formula, and as was noted in the report that Sec. Gottlieb had put together, policing is included as part of your shared costs, streetlights are included as part of your shared costs, curb and gutter. So it does beg the question for those that are getting shared costs, are those truly transportation-related items? Or should we be paying for some basic level of road like you typically get at a county or a town level?” Koles said.

So which is it? Mike Koles from WTA recently claimed in a press release that towns get GTA through cost-sharing. Back in January he said the exact opposite at a @WisconsinDOT task force meeting… which we caught on camera. #WIright #justfixit #wibudget pic.twitter.com/iotoj6JOKS

— MacIver News Service (@NewsMacIver) May 13, 2019

Town of Summit (Douglas County)

The Town of Summit in Douglas County, is a great example of a local government collecting more from state taxpayers than it is spending on its roads. It received $191,794 in GTA in 2017 through the mile-based rate, when it only would have been eligible for about $30,000 through the cost sharing formula. That funded all its highway construction ($19,931) and most of its highway maintenance and administration costs ($223,640) – which include salaries and benefits.

According to Koles, Summit also received $89,000 in emergency road funds that year for disaster relief. That, in addition to other smaller amounts of aid, added up to a total of $280,436 in road aids for the year, according to DOR.

Summit’s total transportation-related expenses for the year (all four DOR categories) was only $243,571, which means Summit came out almost $40,000 ahead. Not a bad profit for that local government. The Town of Summit is just one town that has been very successful in getting state taxpayers to fund all its road work. It has a lot of company.

Town of Stephenson (Marinette County)

The Town of Stephenson benefited the most from taking mileage-based option in 2017. It received a flat rate of $2,389 for each of its 212 miles of road, resulting in a total of $467,308 in GTA. Under the cost sharing formula, it would only have received about $170 thousand.

The Town of Stephenson spent $67 thousand less on roads in 2017 than it received in state road aid.

The Department of Revenue shows Stephenson spent $365,486 on highway construction and $467,030 on highway maintenance and administration. According to the town’s budget, the $365 thousand for highway construction went to blacktop and sealing – exactly the kind of work people expect when they think about road funding.

The budget also shows that out of the $467 thousand spend on “maintenance and administration,” $255,000 went to salaries and benefits. Only $35,000 was spent on a line item labeled “roadwork.” And so, in 2017 the Town of Stephenson received $467,308 in general transportation aids from the state and spent $400,486 on what a reasonable person would consider to be road work.

Town of Wascott (Douglas County)

State taxpayers funded 100 percent of the Town of Wascott’s road work in 2017.

Coming in second place in 2017 for the most mileage-based road aid is the Town of Wascott in Douglas County. It got $443,769 in GTA for 201 miles of road. Under the cost sharing formula it would only have gotten about $134 thousand. According to its budget, the town spent $443,674 on highway maintenance and construction (including signage and salt). Apparently Wascott did not have to spend one cent of its own money on road work that year. Everything came from state taxpayers.

Town of Minocqua (Oneida County)

Third place went to the Town of Minocqua in Oneida County. It got $426,042 in GTA that year for its 193 miles of road. The cost sharing formula would have only provided $306 thousand. According to the town’s budget, it spent $326,114 on highway construction that year. It also spent an additional $159,564 on “road materials and supplies.” That brings its total for actual road work to $485,678, meaning state aid paid for almost 88 percent.

State taxpayers funded 88 percent of the Town of Minocqua’s road work in 2017.

The list goes on and on like that, showing that through mileage-based road aid system, the state is already paying for all road construction in most towns in Wisconsin. Combined, Wisconsin’s towns received $308.8 million in road aid in 2017 and spent $220 million of it on road construction. The rest went to other local expenses like public works’ salaries and benefits – not what taxpayers expect when providing road aid to fix roads.