March 26, 2019

Analysis By Ola Lisowski and Chris Rochester

Reforming government benefits programs has been a Wisconsin hallmark for decades, dating back to the administration of Gov. Tommy Thompson. More recently, Gov. Scott Walker built on the welfare reforms of the 1990s with his own slate of policy changes.

With historically low unemployment and abundant opportunity, Evers picks a strange time in Wisconsin history to roll back reforms that put the onus on welfare recipients to at least try to find work. Click To Tweet

The goal all along was to make sure recipients of taxpayer funded benefits knew the help wasn’t free — something would be expected of them in return. That’s an especially reasonable expectation today considering our state’s robust economy and roaring job market.

Gov. Tony Evers’ 2019-21 biennial budget proposal rolls back much of that progress and attempts to reinstate the notion of a “free lunch,” bankrolled by the hard working taxpayers of Wisconsin. Whether it’s minimal work requirements for those on food stamps, tiny contributions for those on government healthcare, or basic work-search expectations for those on unemployment, Evers’ budget opens the treasury door to those who have little interest in working.

Evers picks a strange time in Wisconsin history to roll back reforms that put the onus on welfare recipients to at least try to find work. Our state’s unemployment rate stands at a near-record low of 3 percent, there are more than 100,000 jobs left unfilled, and employers everywhere are desperate for help.

Simply put, there is no excuse for an able-bodied adult who is capable of working to sit on the sidelines. Yet Evers’ budget makes it a whole lot easier to do just that.

Unlike other single-issue analysis pieces on Evers’ budget document that MacIver has published over the past month, welfare reform crosses many agency boundaries. That makes the basics on spending, total positions, and borrowing a bit more complex, as these programs are run by numerous government agencies, including the Department of Health Services (DHS), the Department of Children and Families (DCF), the Department of Workforce Development (DWD), and others.

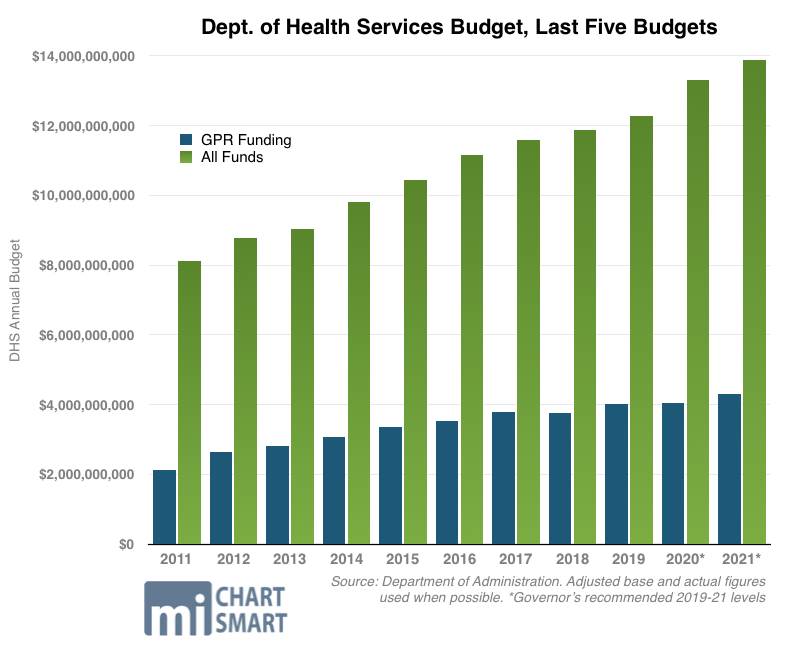

As we wrote in our health care analysis, total spending at DHS, all funds, totals $27.2 billion under the Evers plan. That’s an 11.5 percent or $2.8 billion increase over current spending. Overall government positions in that agency would increase by 192.04 positions total. The budget would spend $8.4 billion in general purpose revenue (GPR), a 6.4 percent increase over the $7.9 billion GPR spent in the current budget. DHS runs programs such as FoodShare and FoodShare Employment and Training (FSET) as well as the behemoth Medical Assistance program that includes BadgerCare.

DCF runs programs like Wisconsin Works, a job training program for low-income parents and pregnant women. All funds spending at the agency would increase by $213 million to $2.83 billion, an 8.1 percent increase. In terms of state dollars alone, the agency would spend $957 million GPR over the biennium, an increase of $27 million or 2.9 percent. Positions at DCF increase by just two full-time equivalents over the biennium, to 988.16 total government jobs at the agency.

DWD runs programs such as unemployment insurance (UI), colloquially known as unemployment benefits. The agency also maintains the Job Center of Wisconsin, which helps employees and employers connect. Under Evers’ plan, all funds spending at DWD would decrease by $20.5 million or 2.9 percent, to $690.5 million overall. Positions at the agency increase by 33.5, to 1,642.55 total in 2021. GPR spending falls to $80.3 million, a decrease of more than $12 million or 13.4 percent. DWD is one of the few agencies that would see a funding decrease under Evers’ plan.

Medicaid eligibility reforms stripped

Welfare reforms enacted under Walker also attempted to nudge people off government health care and into private plans offered through employers.

But a series of critical Medicaid reforms enacted under Walker are also repealed wholesale by Evers’ budget, despite protections enacted during December’s extraordinary session.

Medicaid work requirements largely mirror those for FoodShare benefits and expand on the mantra that people seeking expensive help from their fellow Wisconsinites should be expected to make an effort to be self-sufficient. Click To Tweet

Among the reforms struck by Evers’ budget are work requirements for Medicaid eligibility. Walker increased from 20 to 30 hours a week the time that able-bodied adults (ages 19 to 49) without children must be working, training for work, or looking for work to receive BadgerCare health insurance. That’s the federal maximum, as even Democrats in Congress recognize that 30 hours is not too much to ask for. Evers’ budget rolls that back.

The work requirements largely mirror those for FoodShare benefits and expand on the mantra that people seeking expensive help from their fellow Wisconsinites should be expected to make an effort to be self-sufficient.

Walker had also sought the federal government’s permission to charge a small amount of money for Medicaid benefits for a subset of those below the poverty level. The nominal premiums of $8 for households earning from 51-100 percent of the federal poverty level would give recipients at least a small financial stake in their own benefits and are a step toward reducing the “benefits cliff” that strikes people who climb the economic ladder but are faced with losing generous benefits. Evers’ budget strikes that reform.

The budget also goes easy on child support scofflaws—it eliminates a requirement that Medicaid recipients be in compliance with child support orders.

It also eliminates minor co-pays for non-emergency medical services, and Medicaid Health Savings Accounts are eliminated entirely. Both were enacted with the intent of injecting consumer choice into government health care by forcing recipients to shop around for providers. That, in turn, sought to put a crimp on providers who offered poorer quality services at inflated prices.

FoodShare reforms axed

Walker made welfare reform a focus of his administration, especially as the economy improved and made it easier for people on this program to achieve self-sufficiency.

In April 2015, certain able-bodied individuals had to begin satisfying work and drug screening requirements to receive FoodShare, colloquially known as food stamps. Individuals who did not comply with work requirements for three months in a 36-month period become ineligible for those benefits. Individuals would have to work, receive job training, or a combination of both for an average of 80 hours per month to retain benefits.

In short, they would have to make an effort to earn what the taxpayers of Wisconsin were generously providing them.

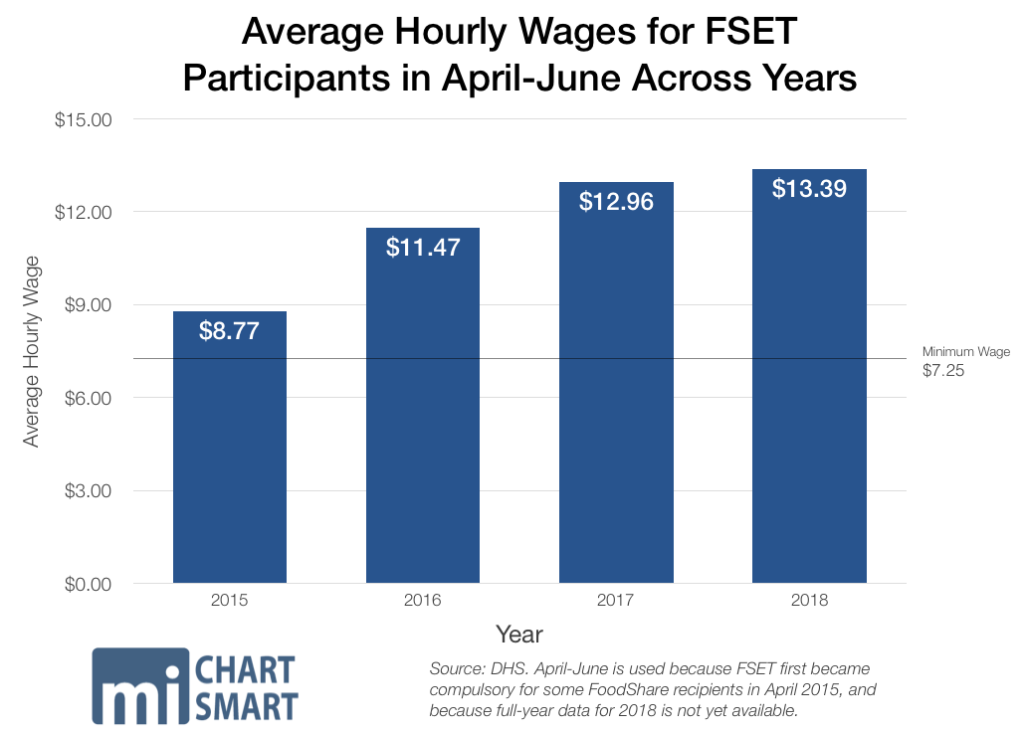

The largest job training program in the state is the FoodShare Employment Training (FSET) program. Wisconsin’s Department of Health Services (DHS) has regularly reported on average FSET wages and weekly hours, both of which have increased consistently. FSET participants earned an average $13.64 per hour, nearly double the state minimum wage, according to the most recent data available.

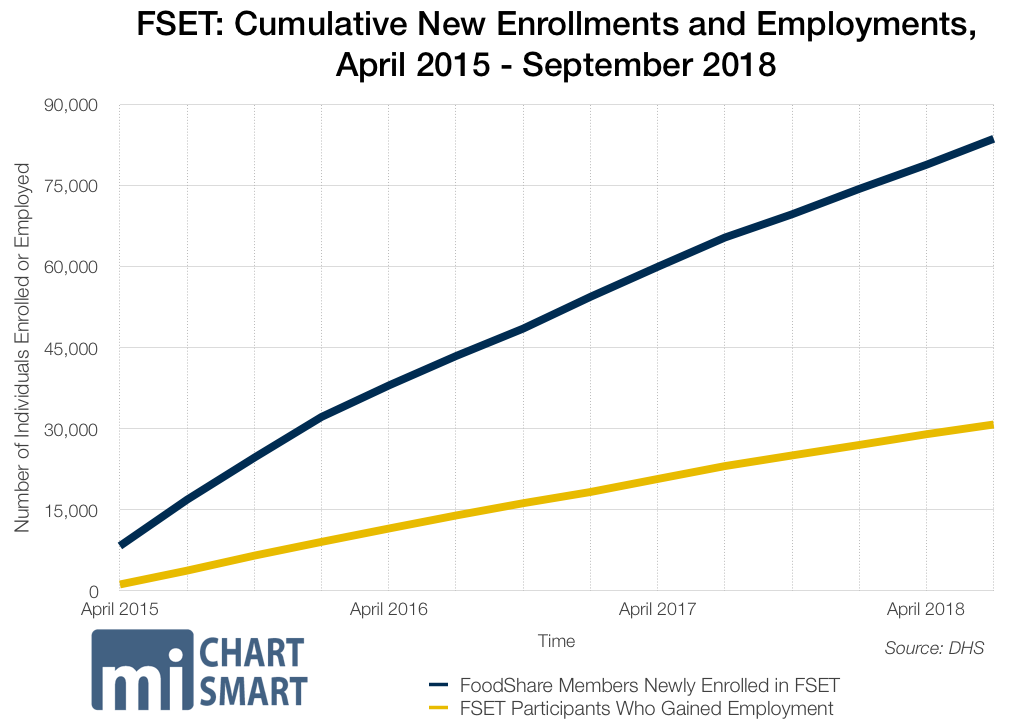

Almost 31,000 FSET participants have gained employment since the state began tracking data in 2015.

Originally, able-bodied adults with no dependents were the only individuals required to work or participate in job training for a total of 80 hours per month. That pool later expanded to able-bodied adults with school-aged dependents (ages six to 18).

Evers’ plan strips back some of the work requirements for FoodShare participants. Able-bodied individuals with school-aged dependents will no longer have to satisfy work requirements; only those without any dependents will still have to comply.

While Evers rolls back the vast majority of welfare reforms made under the Walker administration, keeping work requirements for able-bodied adults without dependants could be considered a casual nod to the success of those reforms. Still, the remaining requirements are a far cry from the robust employment training prioritized under Walker.

In addition, all drug screening requirements are repealed under the proposal. And like in his Medicaid proposal, Evers’ plan also repeals the requirement that individuals be in compliance with child support orders in order to receive FoodShare benefits.

Easier to stay unemployed

A hallmark of Walker’s welfare reform initiatives was to encourage people to find gainful employment and drop off the rolls of government assistance. That not only helped lower costs to taxpayers, Walker and allies argued, but to add to the dignity of people previously dependent on their neighbors. The ultimate goal was to help individuals find a lifelong career that helps them become self-sufficient.

One of the more controversial proposals in Evers’ budget plan would strip back taxpayer protections for unemployment insurance (UI) benefits, making it easier to receive those dollars.

The state unemployment rate has stayed at 3.0 percent for 11 months. UI benefits claims are also at historic lows. But for many, Evers’ budget makes it more comfortable to stay out of the labor force than to find a job. Click To Tweet

Under current law, individuals must wait seven days before qualifying for UI benefits. The waiting period allows state workers to vet the validity of joblessness claims, one protection against fraud. Evers’ plan does away with the waiting period.

Individuals would no longer be required to pass a drug test to receive the benefits, and some job search requirements would be rolled back. It would also increase the maximum rate for UI benefits to $406 per week, from a current maximum of $370.

The state unemployment rate has stayed at 3.0 percent for 11 months. UI benefits claims are also at historic lows. But for many, Evers’ budget makes it more comfortable to stay out of the labor force than to find a job.

The most recent data available show 44,487 Wisconsinites claimed unemployment benefits for the week of March 2, 2019. For the same week in 2009, at the height of the recession, 186,219 Wisconsinites claimed benefits. That’s a remarkable decline in those out of work.

Overall unemployment claims peaked in early 2010 and have steadily fallen since then, with annual peaks occurring every January.

By eliminating welfare reforms for everything from food stamps to unemployment and BadgerCare, Evers’ budget completely reverses the Walker-era ethic of moving people from government dependence to independence.

Instead, his budget attempts to get rid of the notion that while taxpayers are generous, they expect at least a nominal effort in return for their hard-earned dollars.

And it does so at a time of unprecedented opportunity in the private sector in Wisconsin.