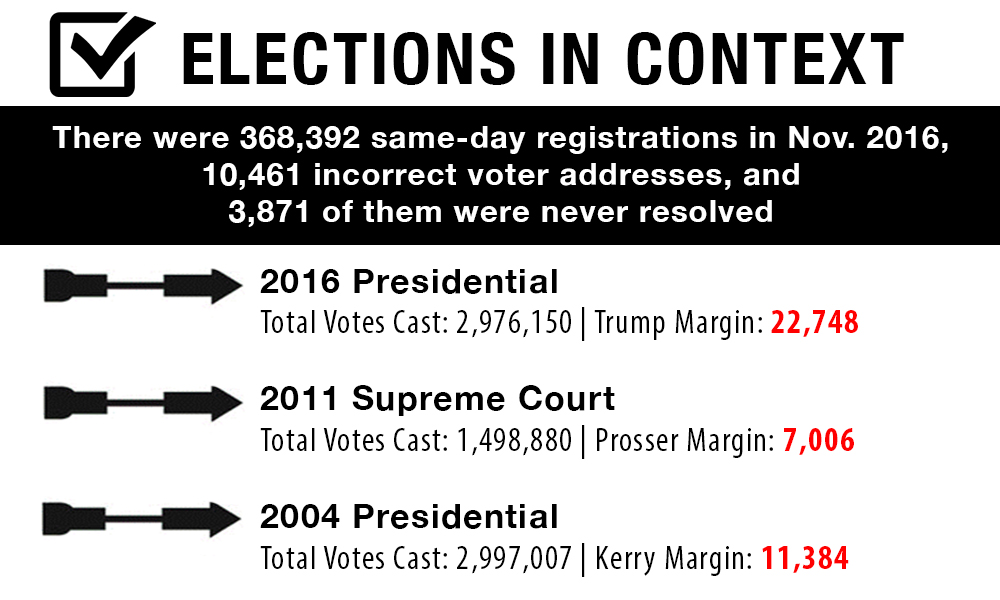

954 Cases Of Voter Fraud Referred to Wisc. DAs After 2016 Election

3,871 cases should have been referred under state law

Total number of fraudulent same day registrations in 2016 General Election could be as high as 10,461

Even though 3,871 WI voters couldn't be verified, only 954 were referred to local district attorneys. According to state officials, all of them should have been referred-- that's the law. #wiright #wipolitics Click To TweetMacIver News Service | June 18, 2018

By Chris Rochester

MADISON, Wis. – Almost a thousand cases of potential election day registration fraud were referred to district attorneys across Wisconsin following the 2016 general election, and questions remain over thousands more voters who can’t be located or verified, according to data from the state Elections Commission.

All together, 368,392 people registered to vote on election day in November 2016. When the state sent postcards to their addresses to verify their residency after the election, 10,461 came back as undeliverable. Local officials claim they were able to reconcile all but 3,871 of them. That means, officially, 3,871 voters in the 2016 election cannot be verified and potentially voted illegally. Unofficially, there could be as many as 10,461 cases of voter fraud from the 2016 election due to election day registrations (EDR) alone.

Municipalities in Milwaukee County take that possibility seriously. A total of 44,797 people registered to vote on election day in Milwaukee County, and 2,563 postcards bounced back. When all was said and done, the City of Milwaukee referred 886 cases of potential voter fraud to the Milwaukee County District Attorney’s office after deactivating the individuals’ registrations. An additional 32 cases were referred by the city of Greenfield, for a total of 918 in Milwaukee County.

Milwaukee County assistant district attorney Bruce Landgraf did not return calls asking how many cases were opened in response to the mountain of referrals following the 2016 election.

If these election day registration postcards are returned because of a bad address, it’s the job of local election officials to correct the data or deactivate the voter’s registration and refer the case to the DA. That’s state law.

Even though 3,871 voters across the state couldn’t be verified, only 954 were referred to the local district attorneys. According to state officials, all of them should have been referred, because that’s the law.

“If the postcard comes back to the municipal clerk as undeliverable, the clerk shall remove the voter from the eligible list and provide the voter’s name to the district attorney’s office,” said state Elections Commission spokesman Reid Magney.

Clerks are also supposed to try correcting problems first, by calling the voter or correcting their information using other documents. “That weeds out people who moved after the election but before the postcards got mailed a month or two later, typographical errors and post office issues that would have made the postcard undeliverable,” Magney said.

Neil Albrecht, executive director of the City of Milwaukee Election Commission, said the city has a policy of investigating returned postcards, then deactivating the registrations that can’t be confirmed by other methods and referring all the cases to the district attorney.

The question is, do the DAs act on the referrals, or do they simply gather dust? Albrecht said his agency isn’t privy to that information.

“Occasionally we learn about whatever investigations occurred, but they have no obligation to report back to us on the status of the cases,” he said.

Somehow, the city of Madison managed to resolve all 842 mismatches without deactivating the registration of a single voter, and without a single referral to the DA.

The city of Madison has the opposite problem. Out of 20,491 same-day registrations, 842 follow-up postcards came back as undeliverable.

Somehow, the city managed to resolve all 842 mismatches without deactivating the registration of a single suspect voter – and without a single referral to the DA.

When asked about their policy for resolving same-day registration problems, Madison elections officials directed MacIver News to the state Elections Commission. A message left with city clerk Maribeth Witzel-Behl was not returned.

Somehow, the city of Madison managed to resolve all 842 same-day registration problems without deactivating the registration of a single voter, and without a single referral to the DA. #ElectionIntegrity #wiright Click To TweetMadison and Milwaukee stand out like hanging chads, but the state is plagued by a patchwork of often conflicting local practices when it comes to deactivating suspect same-day registrations and referring them to the DA. Some local officials follow state law to the letter. Others, not so much.

The city of Janesville automatically deactivates all voters whose cards are returned. Of 3,651 same-day registrations in the 2016 presidential election, 217 follow-up cards came back. All 217 registrations were deactivated. However, their policy for referring suspicious cases to the district attorney is subjective.

“We don’t really have a general policy in place for referrals to the DA,” said Janesville city clerk David Godek. “Typically when we see things that rise to the level of ‘something’s not right here,’ we would refer those to the DA.”

“We had some 17-year-olds that registered to vote in the primaries and we referred those to the DA,” he said.

The small Sawyer County town of Hayward, population 3,279, has a similar policy. Out of 186 same-day registrations, 105 EDR cards were returned, all of which were deactivated. Like Godek, town clerk Bryn Hand said they deactivate the registration for all returned cards, but only refer obvious cases of vote fraud to the DA.

She attributed the large number of bad voter addresses to the town’s “mobile population” – pointing to vacationers and the county’s Ojibwe reservation as possible sources of the bad voter addresses. She said it’s been a while since there was an obvious case of fraud, but recalled the time a man voted both in Hayward and Duluth.

The city of Appleton deactivated the registrations of 94 individuals, but referred zero cases to the Outagamie County DA. And like Madison, city officials referred MacIver News to the Elections Commission.

A staggering 316 municipalities flouted state law, deactivating more registrations than they referred to their DAs, potentially opening the door to thousands of cases of illegal voting.

But the Elections Commission’s Magney pointed to the state law requiring local election officials to refer all individuals whose registrations are deactivated to the DA – clearly not the practice in Appleton and elsewhere.

Local officials “shall change the status of the elector from eligible to ineligible on the registration list, mail the elector a notice of the change in status, and provide the name of the elector to the district attorney for the county where the polling place is located and the elections commission,” states the statue cited by Magney.

But a staggering 316 municipalities flouted that law, deactivating more registrations than they referred to their DAs, potentially opening the door to thousands of cases of illegal voting.

At the very least, it’s further evidence of the slipshod, ad hoc management of Wisconsin’s voter data.

Required checks comparing voter registration information against the Department of Motor Vehicles database provides even more evidence that the voter rolls are packed with bad data and ripe for abuse.

The check routinely turns up errors and mismatched voter data that local election officials are supposed to clean up.

Following the 2016 presidential election, a total of 145,109 voter records compared against DMV data came back with conflicting information. Milwaukee alone had 22,359 voter mismatches. Madison had 10,097; Green Bay had 2,815; Kenosha had 2,073; and Wausau had 1,958 bad records.

College students’ voter records are a particular challenge. According to Elections Commission data, addresses at UW-Milwaukee dorms alone turned up 647 failed DMV checks. That pattern repeats in city after city with college campuses, where voter registration data is teeming with question marks.

The DMV check, required under the federal Help America Vote Act of 2002, is performed any time a new voter is added or any information field in the statewide voter registration database is changed.

“However, the results of the DMV Check do not affect the voter’s eligibility to vote,” Magney said.

Liberals like to claim routine efforts to clean up the voter rolls, like Wisconsin’s law requiring voters be removed from the rolls if they haven’t voted in four years, are covert efforts to disenfranchise low-income and minority people.

According to a 2017 Elections Commission report, Wisconsin mailed out 381,495 notices to people who hadn’t voted in four years following the 2016 election as required by state law, resulting in 351,733 registrations being deactivated.

Only 28,169 voters who were mailed the four-year notice asked for their registration be continued, while 153,416 were returned as undeliverable, and 189,702 voters did not respond to the notice.

Claims by liberals that these routine efforts are burdens to some ignore the growing pile of evidence that vigorous scrubbing of the data is critical to protecting the concept of one-person, one-vote.

And catching and prosecuting people who think otherwise.

Bill Osmulski contributed to this report.